|

Documents sonores Documents sonores

|

Revue de presse Revue de presse

|

Les livres et essais

The books and Essays

|

Publications dont au moins un chapitre évoque "Radio Normandie"

Publications with at least one chapter about "Radio Normandie"

Classement chronologique par année d'édition / Chronological classification by year of publication

|

| |

1930

Brochure (16 pages) éditée par le Radio-Club de Fécamp Brochure (16 pages) éditée par le Radio-Club de Fécamp

( EF8IC - Radio Fécamp & Radio Normandie )

Brochure 16 pages dating from 25.10.1930 - Imp. L. Durand & Fils - Fécamp

cliquer sur la brochure pour l'ouvrir click on the brochure to open it

|

Brochures éditées par la Société "Emissions Radio Normandie"

1932

Brochure de 18 pages - éditée en 1932 Brochure de 18 pages - éditée en 1932

Brochure 18 pages dating from 1932

|

cliquer sur la brochure pour l'ouvrir / click on the brochure to open it

Remerciements à Daniel Lefebvre pour le scan de cette brochure

|

1934

Brochure de 16 pages - éditée en 1934 Brochure de 16 pages - éditée en 1934

(émetteur et studios à Fécamp)

Brochure 16 pages dating from 1934

|

cliquer sur la brochure pour l'ouvrir / click on the brochure to open it

|

1938

Brochure de 28 pages - éditée en 1938 Brochure de 28 pages - éditée en 1938

(éditée en vue de l'inauguration de l'émetteur de Louvetot et les studios à Caudebec-en-Caux)

Brochure 28 pages dating from 1938

(transmitter inauguration of Louvetot and studios for Caudebec-en-Caux)

cliquer sur la brochure pour l'ouvrir / click on the brochure to open it

|

|

1972

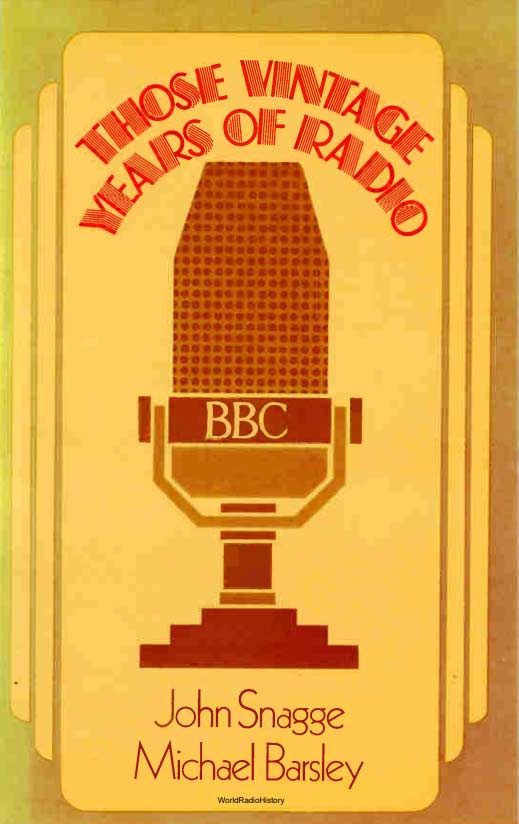

THOSE VINTAGE YEARS OF

RADIO

CES ANNÉES VINTAGE (RETRO) DE LA RADIO

by John Snagge & Michael Barsley

Pitman Publishing 1972

An

excerpt from the chapter on Roy Plomley, English presenter on Radio

Normandie

Un extrait du chapitre relatif à Roy Plomley, présentateur anglais sur

Radio Normandie

|

|

ROY PLOMLEY

Certaines idées d'émissions semblent rester à jamais les bienvenues dans

les programmes de la BBC, car elles

sont

simples, conviviales et populaires. La série “Disques de l'île déserte”,

avec Roy Plomley, a été une véritable bénédiction pour la BBC, en

particulier pour les organisateurs. Elle est diffusée depuis trente ans

et devrait perdurer tant que l'offre de disques et de célébrités

continuera. Quant à la continuité du très affable Roy Plomley, jamais

agacé, jamais irrité, il dissimule son ennui face à un invité ennuyeux

ou égocentrique (...) sont

simples, conviviales et populaires. La série “Disques de l'île déserte”,

avec Roy Plomley, a été une véritable bénédiction pour la BBC, en

particulier pour les organisateurs. Elle est diffusée depuis trente ans

et devrait perdurer tant que l'offre de disques et de célébrités

continuera. Quant à la continuité du très affable Roy Plomley, jamais

agacé, jamais irrité, il dissimule son ennui face à un invité ennuyeux

ou égocentrique (...)

La radio n'était pas une nouveauté pour Roy. Avant la guerre, on parlait

autant de Radio Luxembourg et de Radio Normandie qu'aujourd'hui de

stations “pirates”. (On pourrait le croire, puisque l'un de ses

ancêtres, Francis Plomley, était chirurgien adjoint au XVIIIe siècle) Il

a été décrit comme un pirate de la marine, mais la famille Plomley, bien

que originaire du Devon, a toujours été liée à la médecine. Roy est

devenu l'un des présentateurs et disc-jockeys, non pas à Luxembourg,

mais à Fécamp, en Normandie. Les émissions pouvaient être diffusées de

sept heures du matin à une heure du soir, avec toutes les stars

populaires sur les enregistrements : Tommy Handley, George Formby,

Leonard Henry, Jack Warner, Reginald Foort, etc., sous la direction

énergique du bien nommé capitaine Plugge, député conservateur de Chatham

– le Reith de cette radio.

(John Reith était PDG de la BBC)

Barsley (l'un des auteurs) commente : “Luxembourg et

Normandie étaient bien moins des émissions idiotes que l'actuelle BBC

Radio One, qui s'enfonce de plus en plus profondément dans le bourbier

populaire, avec des disc-jockeys baragouinant comme des singes et des

scripts bien plus stupides, si je puis dire, que les trucs

d'avant-guerre que j'écrivais pour Radio Luxembourg à la fin des années

1930. Un showman comme Sir Thomas Beecham n'était pas trop fier de

diriger une émission au profit des pilules familiales

(pilules contraceptives), dont la valeur

était d'une guinée la boîte

(soit 1,05 £ en monnaie moderne).

Nous avions même les communistes de notre

côté : les programmes luxembourgeois étaient répertoriés dans le Daily

Worker” * (...)

* Le Daily Worker était le

journal du Parti communiste de Grande-Bretagne |

ROY PLOMLEY

Some program ideas seem to remain forever welcome in BBC schedules

because they are simple, friendly, and popular. The series “Desert

Island Discs”, starring Roy Plomley, has been a real boon to the BBC,

especially to the organizers. It has been running for thirty years and

should continue as long as the supply of records and celebrities

continues. As for the continuity of the polite Roy Plomley, never

annoyed, never irritated, he hides his boredom in the face of a dull or

self-centered guest (...)

Radio

was nothing new to Roy. Before the war, Radio Luxembourg and Radio

Normandie were as much talked about as “pirate” stations today. (One

might think so, since one of his ancestors, Francis Plomley, was an

assistant surgeon in the 18th century.) He has been described as a naval

pirate, but the Plomley family, although originally from Devon, has

always been associated with medicine. Roy became one of the presenters

and disc jockeys, not in Luxembourg, but in Fécamp, Normandy. The

programs could be broadcast from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m., with all the popular

stars on the recordings: Tommy Handley, George Formby, Leonard Henry,

Jack Warner, Reginald Foort, and others, under the energetic direction

of the aptly named Captain Plugge, Conservative MP for Chatham—the Reith

of this radio station. Radio

was nothing new to Roy. Before the war, Radio Luxembourg and Radio

Normandie were as much talked about as “pirate” stations today. (One

might think so, since one of his ancestors, Francis Plomley, was an

assistant surgeon in the 18th century.) He has been described as a naval

pirate, but the Plomley family, although originally from Devon, has

always been associated with medicine. Roy became one of the presenters

and disc jockeys, not in Luxembourg, but in Fécamp, Normandy. The

programs could be broadcast from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m., with all the popular

stars on the recordings: Tommy Handley, George Formby, Leonard Henry,

Jack Warner, Reginald Foort, and others, under the energetic direction

of the aptly named Captain Plugge, Conservative MP for Chatham—the Reith

of this radio station.

Barsley

(one of the authors) comments: “Luxembourg and Normandy were

far less idiotic shows than today's BBC Radio One, which is sinking

deeper and deeper into the popular quagmire, with disc jockeys gibbering

like monkeys and scripts far dumber, if I may say so, than the pre-war

stuff I was writing for Radio Luxembourg in the late 1930s. A showman

like Sir Thomas Beecham wasn't too proud to be running a show for the

benefit of family pills, the value of which was a guinea a box. We even

had the Communists on our side: Luxembourg programmes were listed in the

Daily Worker” (...)

From “Those Vintage Years

of Radio” by John Snagge &

Michael Barsley

Pitman Publishing |

1975

|

|

Independent Radio

L'histoire de la radio commerciale L'histoire de la radio commerciale

au Royaume Uni

par Mike Baron

1975 - Terence Dalton Limited

Telling the story of commercial radio in the United Kingdom. Beginning with the early days of broadcasting with the British Broadcasting Company and then covering early commercial broadcasts to the UK from the continent, the book moves through the pirate era to the then newly arrived independence local radio (ILR) stations arriving around the time of publication. Telling the story of commercial radio in the United Kingdom. Beginning with the early days of broadcasting with the British Broadcasting Company and then covering early commercial broadcasts to the UK from the continent, the book moves through the pirate era to the then newly arrived independence local radio (ILR) stations arriving around the time of publication.

Raconter l'histoire de la radio commerciale au Royaume-Uni. Commençant par les premiers jours de diffusion avec la British Broadcasting Company, puis couvrant les premières émissions commerciales vers le Royaume-Uni depuis le continent, le livre traverse l'ère des pirates jusqu'aux nouvelles stations de radio locales indépendantes (ILR) arrivées au moment de sa publication.

le chapitre sur Radio Normandie - PDF (english - français) le chapitre sur Radio Normandie - PDF (english - français) |

1977

« Radios privées, radios pirates » par Frank Ténot - Eds Denoël 1977 « Radios privées, radios pirates » par Frank Ténot - Eds Denoël 1977

|

|

« En 1926, Fernand Legrand, propriétaire de la Bénédictine construit une station de radio-amateur (indicatif F8IC) à Fécamp. Après des essais à très faible puissance (15 watts) un émetteur de 150 watts est installé dans le salon de Fernand Legrand » (...)

> lire la suite (< ce livre étant épuisé, cliquez pour lire le chapitre consacré à Radio Normandie)

Here is an english translation of the chapter on Radio Normandie Here is an english translation of the chapter on Radio Normandie |

1980

« Histoire de la radio en France » par René Duval - Eds Moreau 1980 « Histoire de la radio en France » par René Duval - Eds Moreau 1980

|

|

« Fernand Le Grand, héritier de la Bénédictine, est assurément l’un des plus anciens amateurs de T.S.F. quand apparaît la radiophonie.

Lorsqu’il préparait son doctorat en droit, avant la première guerre mondiale, il fréquentait assidûment le laboratoire d’édouard Branly installé dans les locaux de l’Institut catholique de Paris. » (...)

> lire la suite (< ce livre étant épuisé, cliquez pour lire le chapitre consacré à Radio Normandie)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

"Fernand Le Grand, heir to the Benedictine monastery, was certainly one of the earliest Wireless enthusiasts when radio first appeared.

When he was preparing his doctorate in law, before the First World War, he was a regular visitor to Edouard Branly's laboratory at the Institut Catholique de Paris".

Here is an english translation of the chapter on Radio Normandie Here is an english translation of the chapter on Radio Normandie |

|

1980

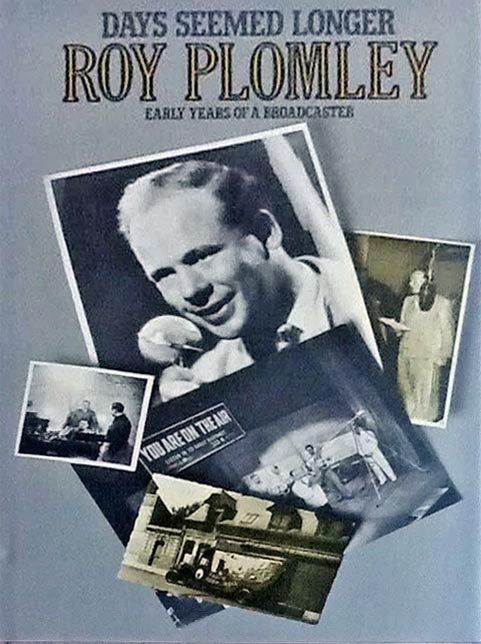

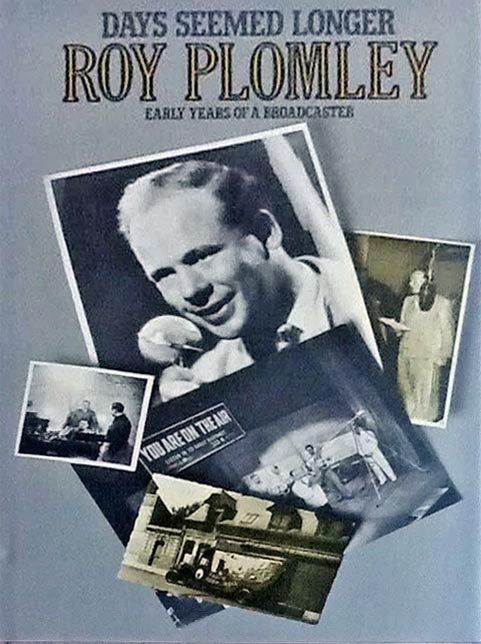

« Days seemed longer » by Roy Plomley - Eds Eyre Methurn - London « Days seemed longer » by Roy Plomley - Eds Eyre Methurn - London

Early Years of a Broadcaster

"Les Jours semblaient plus longs" par Roy Plomley

Les premières années d'un homme de radio (Présentateur à Radio-Normandie)

|

|

La première autobiographie d'un des présentateurs radio les plus célèbres. Lorsque Roy Plomley a eu l'idée de « Desert Island Discs » (à la BBC) en 1941, il n'aurait jamais imaginé qu'il deviendrait l'animateur radio le plus ancien de Grande-Bretagne et qu'une invitation à son programme deviendrait l'un des signes distinctifs de son succès. Roy retrace sa vie depuis sa naissance au-dessus d'une pharmacie à Kingston upon Thames jusqu'à sa sortie dramatique de la France envahie en juin 1940. Il raconte pour la première fois l'histoire intérieure de la radio commerciale d'avant-guerre. Une histoire de vie intime et très intéressante qui comprend des photographies familiales privées jamais publiées auparavant.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The first autobiography of one of radio's most celebrated presenters. When Roy Plomley came up with the idea of 'Desert Island Discs' in 1941, he never dreamed he would become Britain's longest serving radio host and that an invitation to his programme would become one of the hallmarks of success. Roy traces his life from birth above a chemist shop in Kingston upon Thames to his dramatic exit from invaded France in June 1940. He tells for the first time the inside story of pre-war commercial radio. An intimate and most interesting life-story which includes private family photographs never previously published. |

| jeanine |

1982

|

|

LOUVETOT

ma commune

en pays de Caux

( my City in the Country of Caux )

par Jeanine Lebaillif

Edité par le parc naturel régional de Brotonne (1982)

Published by the regional natural park of Brotonne (1982)

|

Voici le chapitre consacré

au Centre émetteur de radio

à Louvetot

(...)

L’origine

Fernand Le Grand, petit-fils d’Alexandre Le Grand, fondateur de la célèbre Bénédictine de Fécamp, créa le radio-club de Fécamp en 1924. Il devint ensuite Radio-Normandie. L’installation encombrait la propriété de Fernand Le Grand : « Vincelli la Grandière ». Le président de Radio-Normandie obtint l’autorisation en 1935 de transférer ses installations au château de Caudebec en Caux. Cette superbe demeure, près de la Seine, reçut l’aménagement des studios, accueillit les vedettes qui animaient Radio-Normandie. Mais ces studios ne suffisaient pas, il fallait leur adjoindre un centre émetteur. Louvetot fut choisi comme étant l’un des sites les plus élevés de la région cauchoise. Fernand Le Grand y acheta un terrain de 3 hectares, situé sur la route Yvetot-Caudebec et fit construire les bâtiments nécessaires à Radio-Normandie.

Les travaux

La première pierre fut posée le 30 novembre 1935. L’ensemble en briques, pierres et colombage, couvert de tuiles rouges avait, à l’origine, une assez belle allure et restait dans le style de construction régionale. Le pylône, de 170 mètres* de hauteur, avait la forme d’un losange allongé et svelte. L’émetteur de Louvetot était relié à Caudebec par un câble de 6 km passant à travers la forêt de Maulévrier.

|

This is the chapter dedicated

to the Radio transmitter center

in Louvetot

The origin

Fernand Le Grand, grandson of Alexandre Le Grand, founder of the famous Bénédictine de Fécamp, created the Fécamp radio club in 1924. It then became Radio-Normandie. The installation cluttered the property of Fernand Le Grand: "Vincelli la Grandière". The president of Radio-Normandie obtained authorization in 1935 to transfer his facilities to the Château de Caudebec en Caux. This superb residence, near the Seine, received the development of the studios, welcomed the stars who animated Radio-Normandie. But these studios were not enough, it was necessary to add a transmitting center to them. Louvetot was chosen as one of the highest sites in the Cauchoise region. Fernand Le Grand bought 3 hectares of land there, located on the Yvetot-Caudebec road and had the buildings necessary for Radio-Normandie built.

The works

The first stone was laid on November 30, 1935. The brick, stone and half-timbered complex, covered with red tiles, originally looked quite nice and remained in the regional building style. The pylon, 170 meters* high, had the shape of an elongated and slender diamond. The Louvetot transmitter was linked to Caudebec by a 6 km cable passing through the forest of Maulévrier.

|

* Le 1er pylône en 1937 (H : 154 m - avec possibilité d'extension télescopique de +/— 20 m supplémentaires selon la longueur d'onde)

* The first pylon in 1937 (H: 154 m - with the possibility of telescopic extension of +/- 20 m additional depending on the wavelength used)

|

La triste destinée de Radio-Normandie

Le tout fut achevé en 1937. Radio-Normandie emménagea en 1938 et la mise en service eut lieu le 12 décembre la même année. L’inauguration, le 4 juin 1939, fut grandiose et de caractère champêtre.

Malheureusement, quelques mois plus tard, la guerre éclatait. L’état, d’abord, puis l’armée allemande réquisitionnèrent le centre émetteur de Louvetot. On badigeonna la façade des bâtiments en guise de camouflage. Le pylône attirait les avions et le bâtiment principal porte encore les blessures des obus et des balles. En 1943, vers une heure du matin, un avion allemand heurta le pylône et alla s’abattre dans un champ du Vieux-Louvetot. Le pylône fut écourté mais tint bon. A la fin de la guerre, avant de quitter les lieux, les allemands le firent tomber.

Il fut reconstruit en 1949 mais avec seulement 120 m de hauteur et tout droit. Il pesait 40 tonnes.

Les émissions reprirent en relais de Paris jusqu’au 30 septembre 1974 à 22 heures. Mais le centre émetteur perdit d’abord sa voix puis il perdit son pylône qui s’abattit le 27 janvier 1977 à 10 heures du matin. |

The sad destiny of Radio-Normandie

Everything was completed in 1937. Radio-Normandie moved in in 1938 and the commissioning took place on December 12 of the same year. The inauguration, on June 4, 1939, was grandiose and rural in character.

Unfortunately, a few months later, war broke out. First the State, then the German army requisitioned the transmitting center of Louvetot. The facades of the buildings were painted as camouflage. The pylon attracted planes and the main building still bears the wounds of shells and bullets. In 1943, around one o'clock in the morning, a German plane hit the pylon and went down in a field in Vieux-Louvetot. The pylon was cut short but held firm. At the end of the war, before leaving the place, the Germans knocked him down.

It was rebuilt in 1949 but only 120 m high and straight. It weighed 40 tons.

Broadcasts resumed in relay from Paris until September 30, 1974 at 10 p.m. But the transmitting center first lost its voice and then it lost its pylon which fell on January 27, 1977 at 10 am. |

Démolition du pylône en 1977 - Demolition of the pylon in 1977

|

Avec sa disparition, Louvetot perdit son originalité et son point de repère. De jour, on l’apercevait de loin ; de nuit, ses lumières rouges et blanches semblaient une double rangée de perles.

(...)

Jeanine Lebaillif |

With his disappearance, Louvetot lost his originality and his point of reference. By day it could be seen from afar; at night, its red and white lights looked like a double row of pearls.

(...)

Jeanine Lebaillif

|

Poème extrait du livre "Louvetot, mon village en pays de Caux" de Mme J. Lebaillif (1982)

TRIBUTE TO LOUVETOT TRIBUTE TO LOUVETOT

Look on the board

This radio pylon,

Red and white hyphen

From the sky to the houses!

This village is Louvetot.

But see how beautiful it is!

Admire this sumptuous greenery.

The farms are surrounded

by superb beech groves.

They undulate the fields

That the wind caresses!

The blue slate roofs

huddle close to the bell tower.

Did you see the ordeal?

This iron lace.

Ah! how pretty it is

against a background of gray sky!

Shaded paths wind along the meadows.

The indolent cows

of grass are satisfied.

Listen to this clear sound

Someone is striking the iron.

The blacksmith, very early on,

Must shoe the horses.

If at Vieux-Louvetot,

Henri IV fought,

Today the birds

sing in the thickets.

Listen to the cuckoo

At the Gîte and at the Black hole,

The frogs near the ponds,

On the road to Flamare,

And the whistling blackbird

In the flowering apple trees.

And when everything sleeps at night

That the moon shines in the sky,

How good it is to breathe

The smell of the white apple trees

And taste in peace

This infinite happiness

That nature makes

For those who appreciate it.

Don't touch my Louvetot

Don't touch it, I love it too much.

Don't destroy its greenery.

The joy of living there and its pure air.

Voir également : https://www.louvetot.fr/louvetot/

|

1983

Broadcasting and Society 1918-1939

par Mark Pegg

https://www.routledge.com/Broadcasting-and-Society-1918-1939/Pegg/p/book/9781032641546

|

Broadcasting and Society (1983) explore le pouvoir de la radio en tant que moyen de communication instantanée et de divertissement. Il s'agit d'un examen détaillé et critique des changements sociaux apportés par la radio au cours des années cruciales et formatrices entre 1918 et 1939 - si la radiodiffusion a réussi à mieux informer les gens, à présenter des intérêts plus larges et à influencer le comportement social.

Broadcasting and Society (1983) examines the power of radio broadcasting as a medium of instant communication and entertainment. It is a detailed and critical examination of the social changes brought about by radio broadcasting in the crucial and formative stages between 1918 and 1939 – whether broadcasting was successful in keeping people better informed, in introducing wider interests, and its influence on social behaviour.

|

Paragraphe où Radio Normandie est mentionnée | Paragraph mentioning Radio Normandie |

Résultats de sondage d’écoute

des radios commerciales en

Grande-Bretagne dans les années 30

(Broadcasting and Society - Mark Pegg)

Comme aux États-Unis, la principale motivation des organismes de radiodiffusion commerciale est d'attirer des revenus publicitaires. Pour vendre du temps d’antenne à des tarifs élevés et susciter l'intérêt commercial, il est essentiel de déterminer quelles sont les heures de grande écoute. L'influence américaine s'est fortement imposée sur le marché britannique. Parmi les entreprises engagées dans les sondages d'opinion figurent Gallup et Crossley aux États-Unis. Ils sont d’abord employés par les deux rivaux européens diffusant vers la Grande-Bretagne Radio Luxembourg et Radio Normandie. (...) La station de l'International Broadcasting Company, Radio Normandie, a collecté des informations sur l'audience dès 1935. Comme preuve, le propriétaire de l'IBC, le capitaine Plugge, cite cette enquête à l'appui de son cas. À cette époque, il dispose d’une équipe de douze personnes qui effectuent des appels personnels dans tout le pays. L'enquête porte sur 8 800 foyers dont 79 % disposent d'un poste : 62 % d’entre eux déclarent écouter l’IBC, sans toutefois préciser de détails. Plugge présente les choses de manière trompeuse. Son argument selon lequel les plus grandes concentrations d'auditeurs se trouvent dans le sud et sur la côte sud, où la proximité de l'émetteur rend l'écoute facile, omet le fait que dans le nord, où la réception est mauvaise, voire inexistante, il n'y a pratiquement aucun auditeur d'IBC.

En 1938, Radio Normandie commande un sondage à Crossley Incorporated. Cela produit des preuves d’une plus grande valeur. Les résultats sont analysés par jour et par heure. En semaine, 64 % des auditeurs avant 11h30 écoutent les stations commerciales, même si l'audience ne représente à l'époque que 30 % du nombre total d’auditeurs. À 17 heures, 44 % des postes sont en service, dont 36 % seulement écoutent les stations étrangères. C’est le dimanche que se déroulent les écoutes à grande échelle comme l’a montré le Variety Listening Barometer. Le matin, 52 % des postes sont utilisés, dont 82,1 % écoutent des chaînes étrangères. Après 12 heures, 66 % des postes sont davantage utilisés et avant 18 heures, 70,3 % écoutent des émissions commerciales. Cela confirme les recherches de la BBC. L'enquête conclut que la concentration pour Radio Normandie se situe à Londres et dans les Home Counties ; Radio Luxembourg dispose d'un émetteur plus puissant et d'une zone de réception beaucoup plus large. En semaine, ces deux stations ont des niveaux d'écoute à peu près équivalents. Normandie a le plus d'auditeurs, mais le dimanche, Luxembourg a de loin la plus grande audience de Grande-Bretagne. La nécessité de vendre du temps d'antenne publicitaire signifie que le temps d'écoute est toujours plus important pour les stations commerciales que pour la BBC. C’est donc à leur avantage qu'il existe une grave imperfection dans l’offre de service de la BBC qui s’explique par la restriction de ses heures de diffusion.

Avant 1939, les émissions de la BBC ne démarrent pas avant 10h30 donnant ainsi aux stations commerciales et autres stations étrangères une diffusion gratuite tôt le matin. Les week-ends sont le principal point noir. Le dimanche, beaucoup de limites sont imposées à la BBC, notamment l’interdiction par les agences de presse, de diffuser des résumés d’information. De plus, il y a la restriction auto-imposée pour éviter tout conflit avec les services religieux. Pendant ces nombreuses heures de non-concurrence, les sociétés de radiodiffusion commerciales réalisent que ces limitations leur offrent une excellente opportunité de fournir un service au moment où les gens en mesure d'écouter n'ont pas accès aux émissions de la BBC. (...) |

Results of commercial radio audience

surveys in Great Britain in the 1930s

(Broadcasting and Society - Mark Pegg)

As in the United States, the main motivation for commercial broadcasters was to attract advertising revenue. In order to sell airtime at high rates and generate commercial interest, it is essential to identify prime time. American influence has been very strong in the UK market. Among the companies involved in opinion polling are Gallup and Crossley in the United States. They were first employed by the two European rivals broadcasting to the UK, Radio Luxembourg and Radio Normandie. (...) The International Broadcasting Company's station, Radio Normandie, collected audience data as early as 1935. As evidence, the owner of the IBC, Captain Plugge, cited this survey in support of his case. At the time, he had a team of twelve people making personal calls all over the country. The survey covered 8,800 households, 79% of which had a radio: 62% of them said they listened to the IBC, although they didn't give any details. Plugge's presentation is misleading. His argument that the greatest concentrations of listeners are in the south and on the south coast, where proximity to the transmitter makes it easy to listen, overlooks the fact that in the north, where reception is poor or even non-existent, there are very few listeners.

In 1938, Radio Normandie commissioned a survey from Crossley Incorporated. This produced more valuable evidence. The results are analysed by day and time. On weekdays, 64% of listeners before 11.30 a.m. listened to commercial stations, even though the audience represented only 30% of the total number of listeners at the time. At 5 p.m., 44% of stations are in service, with only 36% listening to foreign stations. The Variety Listening Barometer shows that Sunday is the day for large-scale listening. In the morning, 52% of sets are in use, 82.1% of which listen to foreign channels. After 12pm, 66% of sets are used more and before 6pm, 70.3% listen to commercial programmes. This confirms the BBC's research. The survey concludes that the concentration for Radio Normandie is in London and the Home Counties; Radio Luxembourg has a more powerful transmitter and a much wider reception area. On weekdays, these two stations have roughly equivalent listening levels. Normandy has the most listeners, but on Sundays, Luxembourg has by far the largest audience in Britain. The need to sell advertising time means that commercial stations always get more listening time than the BBC. It is to their advantage, therefore, that there is a serious imperfection in the BBC's service offer, which is explained by the restriction of its broadcasting hours.

Before 1939, BBC broadcasts did not start before 10.30am, giving commercial and other foreign stations free early morning broadcasting. Weekends were the main problem. On Sundays, many restrictions were imposed on the BBC, including a ban on news agencies broadcasting news summaries. In addition, there is the self-imposed restriction to avoid any conflict with religious services. During these many hours of non-competition, commercial broadcasters realise that these limitations offer them an excellent opportunity to provide a service at a time when people who are able to listen do not have access to BBC broadcasts. (...) |

|

| |

1984

Allo ! Allo ! Ici Radio Normandie !

Une brochure de Jean Lemaître Une brochure de Jean Lemaître

(Editions Durand - Fécamp) éditée par l'Association "Les Amis du Vieux Fécamp"

Cliquer sur la brochure (texte en français)

> English version < > English version <

|

ATTENTION A LA CONFUSION !

Dans sa brochure originale page 9, Jean Lemaître confond allègrement les deux sigles : "BBC" (British Broadcasting Corporation), la radio publique, avec "IBC" (International Broadcasting Company) la société privée chargée des émissions anglaises de Radio Normandie, ce qui n'est évidemment pas la même chose !

La grande rivale, la BBC organisme étatique officiel jouissant de son monopole de radiodiffusion, était opposée aux thèses de la radio commerciale et s'interdisait toute forme de publicité sur ses ondes. Bien évidemment en 1931, il n'y eut aucun contrat de partenariat passé entre elle et la Société des Émissions Radio Normandie ! On se demande pour quelles raisons y aurait-il eu un tel accord ? La similitude des deux sigles BBC et IBC n'était d'ailleurs nullement une coïncidence mais était voulue par le Capitaine L. Plugge directeur de l'IBC, désirant leurrer - au début tout au moins - les publicitaires britanniques timorés pensant ainsi s'adresser à l'organisme officiel de radiodiffusion, pour acheter du temps d'antenne.

jcd

|

Cette brochure "Ici Radio Normandie" a fait l'objet

d'un article promotionnel dans l'hebdomadaire normand

"Le Courrier Cauchois" (en 1984)

|

This brochure "Ici Radio Normandie" was the subject

of a promotional article in the Norman weekly

"Le Courrier Cauchois" (in 1984)

|

|

"Here Radio - Normandy"

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Friends of Old Fécamp Revive

Pre-War Radio Hits

The old Cauchois have not forgotten Radio Normandie, a station born from the energy of a man, Fernand Le Grand, and a few Fécampois who created the first Radio Club in our region.

Mr. Jean Lemaître, president of the Friends of Old Fécamp, has just revived Radio Normandie through a small book (which can be found at the Fécamp tourist office and in the Maison de la Presse) in which he has brought together documents and his personal memories of this great era that local radio enthusiasts dream of recreating today, when so many private stations have emerged with varying degrees of success.

< Photo : The founder of Radio Normandie, Fernand LE GRAND

It was in 1926, Mr. Lemaître reminds us, that Fernand Le Grand set up a transmitter under the call sign EF8IC. Armed with the authorization of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, Radio Normandie began its first broadcasts, but it was not until 1929 that a government decree officially recognized the rights of the Fécamp transmitter and placed it among the twelve private French stations.

Radio Normandie, for all the Cauchois, it was Aunt Francine who was to become the first female announcer in France and who was none other than the sister of Jean Lemaître. Then came Uncle Roland and the Association of Little Listeners was created, which was to reach in a short time some 30.000 members, in addition to the many adults who listened to Radio Normandie. A theatre group was established in 1932, the year when Radio Normandie established relays throughout the department, then as far as Paris from the High school of Posts. New sections were also created in Caen, then Trouville and Deauville.

It was also in 1932 that Henri de France, one of the pioneers of television, came to Fécamp invited by Fernand Le Grand. He made several television broadcasts in the premises of rue Georges-Cuvier, where Aunt Francine was seen for the first time on the small screen.

In 1935, a decree allowed the transfer of the station to Louvetot and the real radio castle was born, which can still be seen on the side of the road from Yvetot to Caudebec-en-Caux. Fernand Le Grand had made Radio Normandie a model station for producing quality broadcasts where talented artists such as Henri Laverne could be heard. Adrienne Gallon, Marie Dubas, André Bellet... Names that will come back to the memory of the Cauchois when leafing through Jean Lemaître's book. He will make them relive for a moment the beautiful epic of this Norman radio that everyone will dream maybe to see one day re-become what she was, thanks to new wave enthusiasts.

< Photo : Aunt Francine

|

|

1985

"Radio Normandie et le défi lancé par l' IBC au monopole de la BBC"

"Radio Normandie and the IBC Challenge to the BBC Monopoly"

par / by DONALD R. BROWNE, The University of Minnesota

Traduction en français | Traduction en français |  Original English Texte Original English Texte

|

1992

“SELLING THE SIXTIES” par Robert Chapman

Vendre les années 60 : Les pirates et la musique pop Radio

Édition en Anglais de Robert Chapman

lien / link > https://monoskop.org/images/6/65/Chapman_Robert_Selling_the_Sixties_The_Pirates_and_Pop_Music_Radio.pdf

|

EXTRAITS des deux paragraphes où l'auteur mentionne "Radio Normandie"

Le modèle commercial de promotion

Leonard Plugge, ancien ingénieur-conseil du métro de Londres et plus tard député conservateur des villes de Medway, n'était manifestement pas accablé par les préoccupations intellectuelles de la BBC au cours de ses années de formation. En 1931, il conclut un accord de parrainage avec la société néerlandaise Philips qui développe les autoradios Philco, et Essex Motors (qui fait partie du groupe General Motors), dans le cadre duquel il doit faire des démonstrations pratiques de l'efficacité des autoradios lors de ses déplacements en Europe. A Fécamp en Normandie, il lance un service en anglais sur l'une des petites radios commerciales qui viennent de commencer à émettre en France. Sans surprise, parmi les premiers annonceurs figurent Dunlop et Philco. Leonard Plugge est un entrepreneur avisé qui voit dans ces nouvelles radios, un potentiel de maximisation des profits. Ce qui commence par un accord réciproque visant à vendre de nouvelles technologies à un nouveau marché a rapidement prospéré avec la création de l'International Broadcasters Club (IBC), un cartel commercial chargé de l'achat et de la vente de temps de sponsoring sur Radio Normandie et sur les autres stations commerciales émergentes, comme le Poste Parisien, Radios Lyon et Toulouse. Le quasi-monopole de vente de l'IBC est considérablement renforcé en 1934 lorsqu'elle devient également responsable de la vente d’espaces publicitaires sur la nouvelle Radio Luxembourg.

Les premières critiques de Luxembourg et de Normandie portent sur leur amateurisme, (comparé au professionnalisme de la BBC) et l'irrégularité de leurs émissions, tandis que les tenants de la haute morale indiquent qu'il y a quelque chose de désagréable, si ce n'est à propos de la publicité sur les ondes en soi, du moins à propos d’une sorte de palliatifs de mauvaise qualité promus. En 1934, 90 entreprises font de la publicité pour leurs produits sur les stations commerciales ; Radio Luxembourg représente 71 % de toutes les publicités, Normandie 17 %. En 1936, Philco, qui détient une part significative dans le développement de la radio commerciale européenne et américaine, commence à doter Radio Luxembourg du système d'enregistrement Philips-Miller, le son enregistré sur film. Ce système, précurseur de l'enregistrement sur bande magnétique, est de loin plus avancé que tout ce que la BBC utilise à l'époque. Il est également utilisé par J. Walter Thompson, la plus grande agence de publicité au monde, pionnière du sponsoring radio. Luxembourg réalise ainsi la compatibilité des systèmes technologiques avec ses partenaires commerciaux dans ses trois premières années d’existence. En 1936, l'approche cavalière de Leonard Plugge n'est plus à la mode et, avec l’imminence d'installations de radiodiffusion plus puissantes, Radio Luxembourg se lance dans son propre expansionnisme. Après avoir remporté un procès coûteux, intenté par Plugge pour rupture de contrat, les dirigeants luxembourgeois rompent tout lien avec l'IBC. En 1937, les entreprises donnent pour instruction à leurs agences de faire de la publicité sur Radio Luxembourg, menaçant d’exporter leurs comptes lucratifs ailleurs si les agences ne s’y conforment pas. Cadbury et Reckitts ont tous deux adopté cette stratégie promotionnelle par l’intermédiaire de leur média britannique, le London Press Exchange. D’autres contrats lucratifs en provenance des États-Unis suivent bientôt, avec Ford Motors, Colgate Palmolive contribuant à façonner à la fois le divertissement radiophonique et le consumérisme de masse avec les capitaux américains. Des sociétés britanniques telles que Rowntree, Stork et McDougall deviennent également des noms familiers au Luxembourg et en Normandie. En plus d'avoir subi des pressions de la part des annonceurs au cours des années 1930, les stations commerciales constatent que l'Association des propriétaires de journaux n'est pas plus complaisante avec elles qu'elle ne l'a été envers la BBC. Le comité Sykes de 1923 comprend des représentants du NPA (association des éditeurs chargée de la distribution des journaux) et condamne sans surprise l'utilisation de la publicité pour financer la BBC, craignant qu'une telle méthode de financement n'entraîne une concurrence avec les journaux pour leurs revenus publicitaires. Avec l'arrivée de nouveaux concurrents étrangers, la NPA refuse de distribuer tout journal faisant la promotion ou publiant les grilles de programmes des stations commerciales. Les publications favorables à la cause commerciale, comme le Sunday Referee, sont effectivement évincées par un tel abus de pouvoir. Alors qu'il entretient de bonnes relations avec Radios Paris, Normandie et Luxembourg, offrant même à ses propres annonceurs des espaces sur les stations commerciales, le Sunday Referee triple sa diffusion, mais dans les deux ans qui suivent l’ultimatum du NPA, il fusionne avec le Sunday Chronicle.

L'intervention politique et économique directe joue un rôle majeur dans le développement du secteur commercial. Dans les années 1930, ni Radio Toulouse ni Radio Lyon ne peuvent rivaliser avec les succès comparatifs de Radio Normandie et de Radio Luxembourg. Toutes deux sont entravées par l'incapacité de négocier des heures de transmission en journée avec la Grande-Bretagne (Ndw : pas de propagation le jour). Même avec la force d'un cartel commercial, l'autre filiale de l'IBC, Radio Paris découvre qu'une fréquence en ondes longues, un puissant émetteur de 60 kw et une diffusion illimitée pendant la journée ne sont pas suffisants pour supporter l'arrivée d'un nouveau concurrent en raison d'une obligation imposée par la loi envers son public local. Radio Paris est repris par le gouvernement français en avril 1933, et les programmes sponsorisés prennent fin en novembre. Les Pays-Bas ont déjà interdit le parrainage en 1930 ; la Belgique suit en 1932. Ailleurs en Europe, l'Autriche, le Danemark, la Hongrie et la Yougoslavie n'autorisent pas la publicité sur leurs radios. Au printemps 1939, seules les stations luxembourgeoises et quelques stations françaises diffusent de la publicité.

(...)

La programmation

Avant le déclenchement de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les radios luxembourgeoises et normandes représentent entre 50 et 80 % de l'écoute du dimanche aux heures de grande écoute au Royaume-Uni. En 1938, les divertissements légers représentent plus d'un tiers de leur temps de programmation. La musique de danse, les variétés et les revues ne représentent que 10 % de la production de la BBC, et parmi cette maigre proportion, seules les formes de musique les plus inoffensives sont jouées, la BBC privilégiant les styles continentaux plutôt que la musique de danse. Le jazz est souvent traité avec un mépris raciste à peine dissimulé. En 1935, le terme « hot jazz » est interdit ; la BBC décide qu'il doit plutôt être appelé jazz « brillant » ou « swing ». Le chant « Scat » est totalement interdit. En 1938, la BBC diffuse son tout premier concert de danse un dimanche, et au moment où le couvre-feu culturel de John Reith (directeur général de la BBC) le jour du sabbat est levé, Radio Luxembourg rapporte que son audience a considérablement diminué. Le style de diffusion sobre et formel institué au cours des années où John Reith dirige, avec ses annonceurs en smoking, ses sermons et son Shakespeare le dimanche, pour « donner aux gens un peu plus que ce qu'ils veulent», reflète un héritage puissant, un héritage culturel qui est crucial pour une compréhension plus large du fonctionnement de la BBC et la façon dont il a initialement abordé l’offre de divertissement léger. L’austérité et le leadership moral qui a caractérisé les premières années de la BBC n'était pas simplement le caprice d'un homme qui a connu une éducation presbytérienne stricte et qui maintenant est responsable d'un système de radiodiffusion publique. Ces traits sont inscrit dans les valeurs qui imprègnent la plupart des systèmes éducatifs de la société. Concernant son attitude envers la culture populaire, on a beaucoup parlé de l'antipathie initiale de la BBC à l'égard de la « musique de danse » (laquelle en ces années 1920 et 1930 est synonyme de jazz), comme si ce dédain est propre à la BBC seule. Mais elle ne crée pas de précédent lorsque bon nombre de ses personnalités de premier plan condamnent « les plaisanteries, les chants et le tapage des groupes de jazz». Elle n'est qu'à l'avant-garde d'une campagne qui fait appel à d'éminents chefs d'orchestre symphonique, chefs d'orchestre militaires et autres puristes et esthètes pour leur soutien. La question est également entachée de colonialisme et porte des hypothèses sous-jacentes sur les mérites relatifs des traditions européennes et afro-caribéennes. Même la haine légendaire de Reith pour l'« Américanisation » n'est que le reflet d'une préoccupation plus large au sein du monde culturel.

La promotion d'une hiérarchie culturelle, accompagnée de notions d'évaluation critique, est évidente dans le style de diffusion de la BBC et, jusqu'à la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les contrôleurs de programmes refusent fermement d'adhérer au populisme de leurs concurrents commerciaux. Étant la première ligne de contact entre le public et la BBC, les annonceurs sont des ambassadeurs, des fonctionnaires de la BBC et il leur est strictement interdit de développer leur propre personnalité à l'antenne. Leur style est formel, les programmes sont scénarisés et fortement édités. Les résultats sont souvent censurés. L'improvisation est tout simplement inadmissible ; Selon la doctrine de la BBC, la spontanéité est synonyme de frivolité et d'irresponsabilité. Pendant ce temps, sur les stations commerciales, des lieux sont fantasmés, des orchestres radiophoniques « inventés». Les annonceurs développent une « personnalité » et sont bavards et informels. Ils enchaînent les enregistrements, donnant ainsi aux programmes un semblant de continuité. De tels dispositifs sont écartés au début de la BBC ; même l'idée de « répartir » les programmes sous forme de «séries» quotidiennes ou même hebdomadaires, est rigoureusement découragée. L'écoute est un art raffiné selon les décideurs de la BBC, et chaque élément est censé avoir sa propre valeur, indépendamment de ce qui le précède ou le suit. L'esquisse des procédures formelles de style de programmation décrites ci-dessus suggère que les stations commerciales sont plus en phase avec le public qui les écoute que ne l'est la BBC.

(...)

La campagne publicitaire d'avant-guerre la plus célèbre de Radio Luxembourg pour Ovaltine, présente des sketches interprétés par un groupe d'enfants comédiens de la classe moyenne supérieure au langage impeccable et un présentateur dont le ton est impossible à distinguer de celui diffusé sur la BBC.

Les animateurs des radios commerciales, bien qu’indéniablement aimables et de style amical, sont subordonnés aux diktats du commerce. Comme aux États-Unis, les annonceurs ont tendance à parrainer des émissions entières plutôt que des créneaux individuels ; celles-ci durent de 15 minutes à une heure, et les articles de consommation sont annoncés aux moments de la journée jugés les plus susceptibles de maximiser les ventes. Le sponsor de l'émission matinale de Radio Normandie est par exemple un fabricant de céréales pour petit-déjeuner. Même si, contrairement à son homologue de la BBC, l'annonceur en tant que vendeur est autorisé à développer sa personnalité, le sentiment de fraternité qu'il cultive est fermement contextualisé par le sponsor dont il donne du temps d'antenne aux produits. La plupart des annonceurs se conforment aux contraintes qui leur sont imposées. En effet, l’obéissance collective et l’autorégulation sont devenues les caractéristiques des procédures normatives des radios commerciales. C'est simplement la bureaucratie de la BBC qui est un anathème pour les éléments les plus non-conformistes parmi les annonceurs des stations commerciales. Au cours des années 1940-1941, la BBC commence à s'approprier les techniques et l'expertise de la radio commerciale, en modelant son programme des Forces britanniques sur le successeur de Radio Normandie, Radio Internationale (Fécamp) qui a continué à émettre après le déclenchement de la guerre pour divertir le corps expéditionnaire britannique dans le nord de la France. Ce service financé par le gouvernement britannique, diffuse de nombreux programmes produits par l'agence J. Walter Thompson, autrefois réputée pour son implication dans le secteur commercial. Pour la première fois, du personnel ayant une expérience préalable dans la radio commerciale et les agences de publicité est recruté et une américanisation notable s'est brièvement glissée dans les programmes de la BBC.

(...)

|

Only the 2 paragraphs where the author mentions Radio Normandie

The commercial model of promotion

Somebody clearly not burdened by the highbrow concerns of the BBC in its formative years was Leonard Plugge, a former consulting engineer on the London Underground, and later Conservative MP for the Medway towns. In 1931 he had arranged a sponsorship deal with the Dutch company Philips, which was developing Philco car radios, and Essex Motors (part of the General Motors group), in which he was to give practical demonstrations of car radio efficiency while driving round Europe. At Fécamp in Normandy he initiated an English service on one of the small commercial radio stations which had just started broadcasting in France. Among the first advertisers, not surprisingly, were Dunlop and Philco. Leonard Plugge was a shrewd entrepreneur, who saw in the new facility of radio the potential for profit maximization. What began with a reciprocal deal to sell new technology to a new market rapidly prospered, with the setting up of the International Broadcasters’ Club (IBC), a commercial cartel responsible for the buying and selling of sponsorship time on Radio Normandie, and on the other newly emerging commercial stations, such as Poste Parisien, Lyon, and Toulouse. The IBC’s virtual monopoly of sales was considerably strengthened in 1934 when it became responsible for selling advertising space on the newly formed Radio Luxembourg too.

Early criticism of Luxembourg and Normandie focused on their amateurism, (relative of course to the BBC’s notion of professionalism), and the irregularity of their broadcasts, while takers of the moral high ground indicated that there was something distasteful, if not about advertising on the wireless per se, then about the kind of shoddy palliatives being promoted. By 1934, 90 companies were advertisingtheir goods on the commercial stations; Luxembourg accounted for 71 % of all advertisements, Normandie 17 %. In 1936 Philco, who held a significantly high profile in the development of both European and American commercial radio, began providing Radio Luxembourg with the Philips–Miller system of recording sound on to film. This system, the forerunner of magnetic tape recording, was far more advanced than anything the BBC was using at the time. It was also being utilized by J. Walter Thompson, the largest advertising agency in the world, and a pioneer of radio sponsorship. Luxembourg thus achieved compatibility of technological systems with its commercial allies within three years of coming on air. By 1936 Leonard Plugge’s cavalier approach was out of favour and with the potential looming for more powerful broadcasting facilities Luxembourg embarked upon a little expansionism of its own. After winning a costly court case, instigated by Plugge for breach of contract, Luxembourg’s directors successfully severed all connection with the IBC. By 1937 companies were actually instructing their agencies to advertise on Radio Luxembourg, threatening to take their lucrative accounts elsewhere if the agencies did not comply. Both Cadbury and Reckitts adopted this flexing of promotional muscle through their British outlet, the London Press Exchange. Other lucrative contracts from the USA soon followed, with Ford Motors, Colgate, and Palmolive helping to shape both radio entertainment and mass market consumerism with American capital. British firms such as Rowntree, Stork, and McDougall also became familiar names on Luxembourg and Normandie. As well as experiencing pressures from advertisers during the 1930s the commercial stations found the Newspaper Proprietors’ Association was no kinder to them than it had been to the BBC. The Sykes Committee of 1923 had included representation from the NPA (Chairman Viscount Burnham) and not surprisingly condemned the use of advertising to finance the BBC, fearing that such a method of funding would mean competition with the newspapers for advertising revenue. Withthe advent of the new foreign competitors the NPA refused to distribute any paper which promoted or published the programme schedules of the commercial stations. Smaller publications who were sympathetic to the commercial cause, such as the Sunday Referee, were effectively squeezed out of existence by such power wielding. While it had enjoyed good relations with Radios Paris, Normandie, and Luxembourg, even offering its own advertisers space on the commercial stations, the Sunday Referee had trebled its circulation, but within two years of the NPA ultimatum it had been merged into the larger Sunday Chronicle.

Direct political and economic intervention played a major part in shaping the development of the commercial sector. In the 1930s neither Radio Toulouse nor Radio Lyon was able to match the comparative success of Normandie and Luxembourg. Both were hampered by a failure to negotiate daytime transmitting hours to Britain for their popular music services. Even with the strength of a commercial cartel the other IBC affiliate Poste Parisien found that a long wave frequency, a powerful 60 kw transmitter, and unlimited day-time broadcasting were not enough to survive because of a legislated prior commitment to its home audience. Parisien was taken over by the French government in April 1933, and sponsored programmes were ended in November. The Dutch had already banned sponsorship in 1930; Belgium followed in 1932. Elsewhere in Europe, Austria, Denmark, Hungary, and Yugoslavia permitted no advertising on their radio networks. There was a limited amount on Spanish radio and on Athlone (later Radio Eireann) but by the spring of 1939 only Luxembourg and a few French stations were broadcasting advertisements. Listeners, it seems, could enjoy occasional respite from the BBC’s preached litany of high culture, but these examples underline the extent to which strict legislation and regulation determined the evolution of commercial radio in Europe. In addition to generating revenue the commercial sector, like the state sector, had to generate its own notions of prestige. It did so by nurturing an image of populist underdog. While the BBC promoted the Reithian triumvirate of ‘Educate, Inform, Entertain’ the commercial stations interpreted listeners’ desires in quite a different way, acknowledging public taste, and constructing their audience around the promotion of consumer populism. While courting such appeal in the prewar years Radios Luxembourg and Normandie ran regional talent shows and soap operas, aspects of popular culture largely shunned by the BBC. Luxembourg had also indicated in its original broadcasting manifestothat time would be allocated to ‘interludes’ of speech-based programming. These interludes were to have featured debates and discussions in a far less instructive and formal manner than that adopted by the BBC, but as there was not a sufficient response from advertisers to justify programmes of this kind the idea never came to fruition, and instead listeners were offered canned laughter on band shows, accompanied by a heavily scripted gushing bonhomie, already familiar to American audiences, and similar to the approach which the BBC was later to adopt as part of its genuflection towards populism.

Programming

Before the outbreak of the Second World War Radios Luxembourg and Normandie accounted for anywhere between 50 and 80 % of peak time listening in the UK on Sundays. In 1938, despite the fact that light entertainment was given over a third of its programming time, dance music, variety, and revue provided a mere 10% of the BBC’s output, and among this meagre ration only the most innocuous forms of music were played, the BBC favouring continental styles over dance band music. Jazz was often treated with barely concealed racist contempt by the BBC. In 1935 the term ‘hot jazz’ was forbidden; the BBC decided it should be called ‘bright’ or ‘swing’ jazz instead. ‘Scat’ singing was banned outright. In 1938 the BBC broadcast its first ever dance band concert on a Sunday, and the moment Reith’s cultural curfew on the sabbath was lifted Radio Luxembourg reported that its own audiences dropped significantly. The sober and formal broadcasting style which developed during the years when John Reith was Director-General of the BBC, with its dinner jacket-wearing announcers, sermons and Shakespeare on Sundays, and ‘giving the people a little more than what they want’, reflected a powerful heritage, a cultural inheritance which is crucial to a wider understanding of the functioning of the Corporation and the way it initially approached light entertainment provision. The sobriety and moral leadership which characterized the early years of the BBC were not merely the whim of one man who had experienced a strict Presbyterian upbringing and now just happened to be in charge of a public broadcasting system. These traits were enshrined in the values which permeated most of the dominant educative institutions of society. Concerning its attitude towards popular culture, for instance, much has been made of the BBC’s initial antipathy towards ‘dance music’ (which in the 1920s and 1930s was synonymous with jazz), as if such disdain was particular to the BBC alone. But the Corporation was not setting a precedent when many of its leading figures condemned ‘wisecrack, song, and the blare of the jazz band as next to worthless. It was merely at the forefront of a campaign which could also call upon prominent symphony orchestra conductors, military bandleaders, and other like-minded purists and aesthetes for support. The issue was also tainted with colonialism and carried underlying assumptions about the relative merits of the European and AfroCaribbean traditions. Even Reith’s legendary loathing of ‘Americanization’ was only a reflection of wider concern within the cultural establishment about the predicted erosion of refined European culture by vulgar commercialism.

The promotion of a cultural hierarchy with its accompanying notions of critical evaluation, was apparent in the BBC’s broadcasting style, and up until the Second World War programme controllers steadfastly refused to embrace the populism of their commercial competitors. Being the first line of contact between audience and Corporation, announcers were ambassadors, public servants for the BBC, and were strictly forbidden to develop on-air personalities of their own. Their style was formal, programmes were scripted and heavily edited, and output was often censored. Improvisation was simply inadmissible; according to BBC doctrine spontaneity was synonymous with frivolity and irresponsibility. Meanwhile on the commercial stations locations were fantasized, radio orchestras ‘invented’. Announcers developed ‘persona’, and were chatty and informal. They also linked records, thus giving programmes some semblance of continuity. Such contrivances were shunned during the early days of the BBC; even the idea of ‘slotting’ programmes into daily or even weekly ‘series’ form was rigorously discouraged at first. Listening was a refined art according to the BBC’s decision makers, and each item was supposed to stand on its own merits regardless of what preceded or followed it. The thumbnail sketch of the formal procedures of programming style outlined above suggest that the commercial stations were more in tune with the listening audience than the BBC was. In fact the context in which the commercial stations’ programme ethos developed was no less duty bound. The broadcasting style was certainly more risqué, but its contrived use of the vernacular and the commonplace was as artificial in its way as the BBC’s Received Pronunciation. Nor were the commercial stations free of plummy accents and the well-rounded vowel.

Radio Luxembourg’s most famous prewar advertising campaign, for Ovaltine, featured sketches performed by a group of impeccably spoken uppermiddle-class child actors, and a presenter whose clipped tones were indistinguishable from those aired on the BBC.

Commercial radio announcers, although undeniably amiable and chummy in style, were, unless they displayed creative initiatives above and beyond the call of duty, basically administrators, subordinate to the dictates of commerce. As in the USA, advertisers initially tended to sponsor whole shows rather than single slots; these ranged from 15 minutes to one hour in length, and the consumer items endorsed were advertised at times of day deemed most likely to maximize sales. The sponsor of Radio Normandie’s early morning programme, for example, was a manufacturer of breakfast cereal. Although, unlike his BBC counterpart, the announcer as salesman was allowed to develop a personality, the sense of fraternity he cultivated was firmly contextualized by the sponsor whose products he was giving airtime to. The repertory acting and sales backgrounds of many who went into commercial broadcasting would have prepared them for the formality of speaking well-rehearsed lines scripted by others. Many were jobbing actors, ‘resting’ between parts, and were ideally suited to the ‘jack of all trades’ aspect of their promotional role. Most announcers willingly complied with the constraints that were applied to them. Indeed collective obedience and self-regulation became hallmarks of commercial radio’s normative procedures very early on, and the majority willingly adopted notions of responsibility every bit as restrictive and duty bound as those codes of behaviour nurtured by state regulation. It was merely BBC bureaucracy that was anathema to the more maverick element among announcers on the commercial stations. During 1940–1 the BBC began to appropriate the techniques and expertise of commercial radio, modelling its Forces Programme upon Radio Normandie’s successor, Radio Internationale, which had continued broadcasting after the outbreak of war to entertain the British Expeditionary Force in northern France. This service, financed by the British government, ran many programmes produced by the J. Walter Thompson agency, previously noted for its involvement with the commercial sector. For the first time staff with previous experience in commercial radio and advertising agencies were recruited and a noticeable Americanization briefly crept into BBC programmes. (...) |

1994-2008

Histoire Générale de la Radio et Télévision en France Histoire Générale de la Radio et Télévision en France

par Christian Brochand (édité par La Documentation française)

En 3 tomes :

Tome 1 : 1921 - 1944 *

Tome 2 : 1944 - 1974

Tome 3 : 1974 - 2000

* C'est évidemment le Tome 1 où l'on parle de Radio Normandie qui retiendra notre attention :

œuvre de référence pour l'histoire de la radio/télévision

L'intérêt pour les médias s'accompagna durant de trop longues années d'une injustifiable ignorance de leur histoire. Il fallut donc attendre l'ouvrage magistral de Christian Brochand pour qu'enfin chercheurs, journalistes, politiques, professionnels disposent d'une histoire exhaustive de la radio et de la télévision française. Les risques étaient pourtant nombreux, à la mesure de cette ambitieuse entreprise. Mais l'auteur a su les endiguer pour nous proposer un ouvrage qui satisfera, sans nul doute possible, le curieux comme l'homme averti.

Stéphane Olivesi - La Revue des Revues et des Livres |

> uniquement les chapitres "radio-normandie" en pdf (text in french) > uniquement les chapitres "radio-normandie" en pdf (text in french)

1996

Hier, le Havre (tome 1) Hier, le Havre (tome 1)

Extrait du livre de Jean Legoy (Edition de l'Estuaire - 1996)

Le chapitre : Les Débuts de la Radio au Havre < en pdf (text in french) Le chapitre : Les Débuts de la Radio au Havre < en pdf (text in french)

2000

|

Juste avant la parution de son livre "Et le monde a écouté" en 2008, Keith Wallis avait écrit un article dans le magazine "Best of British" de février 2000...

Les premières émissions en

anglais depuis le continent

Note : rappelons qu'en Grande Bretagne, la publicité est interdite à la BBC et les radios commerciales n'ont été autorisées qu'en 1973. Dans les années 30, pour contourner la loi, il suffisait aux publicitaires britanniques de louer du temps d'antenne sur les stations commerciales du continent entendues au Royaume Uni (Radio Luxembourg, Radio Normandie, Radio Toulouse...) :

"Beaucoup de stations européennes dans les années 30 avaient leurs programmes patronnés par l'International Broadcasting Company (IBC) de Londres. L'IBC était la création du Capitaine L. Plugge qui avait gagné ce grade dans la RAF. Son premier succès avec l'IBC a été Radio Fécamp qui a démarré ses programmes en anglais le 6 septembre 1931. Le premier présentateur était William Evelyn Kingwell, caissier d'une succursale de la National Provincial Bank au Havre. Il se rendit en motocyclette à Fécamp pour passer des disques le dimanche soir de 22 h 30 à 1 h du matin. Trois mois plus tard, c'est devenu Radio Normandy avec Maxy Stanniford et Stephen Williams, d'abord le samedi et dimanche puis finalement chaque jour de la semaine à partir d'avril 1933.

Radio Paris existait depuis 1931 et poursuivait ses programmes en anglais jusqu'au moment où les français en eurent assez d'eux à la fin de 1933. Le Poste Parisien pris la relève jusqu'en 1939. Le directeur des programmes anglais sur Radio Paris, Stephen Williams partit pour Luxembourg à la fin de 1933. L'IBC ne fournissait pas officiellement de programmes à Radio Luxembourg, car la station était engagée avec sa régie publicitaire "Radio Publicity" à Londres, mais ceci est une autre histoire. Une Radio Luxembourg tout à fait différente a vu le jour après la guerre jusqu'à sa fermeture définitive en décembre 1991.

Radio Toulouse démarra en octobre 1931 avec comme présentateur W. Brown-Constable. Tom Ronald le remplaça en 1933 jusqu'à la suspension des émissions en anglais au mois de juillet de cette même année. Ces émissions ont repris un peu plus tard en octobre 1937. On dit qu'Henry Hall était mêlé à ce démarrage.

En ce qui concerne les autres stations, il y en avait beaucoup. Radio Côte d'Azur à Juan-les-Pins démarra en avril 1934 devenant Radio Mediterranée en avril 1937. Ljubliana, Athlone, Union Radio Madrid, San Sebastian, Barcelona, Valencia et Rome, toutes ont mené des émissions en anglais de temps en temps. L'Espagne possédait en outre deux stations sur ondes courtes à Aranjuez et Madrid EAQ. Naturellement, toutes ont fermé à la déclaration de la guerre.

Radio Normandy a continué pendant un moment sous le nom de Radio International pour divertir les troupes(*). Radio Normandy avait inauguré son nouveau centre émetteur à Louvetot en 1938 en grande cérémonie, avec de nouveaux studios à Caudebec-en-Caux. Malheureusement la guerre était déclarée l'année suivante et les Allemands prirent possession des installations. Le château de Louvetot survécut, ce qui n'est pas le cas de Radio Normandy, comme des antennes. Mais c'est une église qui a racheté les installations.

Plusieurs célébrités ont démarré leurs carrières dans ces stations, Roy Plomley, Bob Danvers-Walker (la voix de Pathé News pendant la guerre sur les films d'actualité !), Tom Ronald, Philipp Slessor et Jack Hargreaves pour n'en nommer que cinq. En 1939, l'International Broadcasting Company doit s'arrêter mais elle ouvre à nouveau après la guerre en tant que studios d'enregistrements très renommés. Le Capitain L. Plugge a perdu beaucoup de son investissement (!) dans l'aventure excepté le faible revenu qu'il percevait en tant que député au Parlement britannique. Il avait été élu député conservateur de Colchester en 1935.

L'histoire complète de ces stations de radio des années 30 est racontée dans la biographie que j'ai écrite sur le Capitaine L. Plugge intitulée "And the world listened" ("Et le monde a écouté")** que je publierai... si un éditeur se dévoue ! Une annexe donnent toutes les dates et autres détails sur toutes les stations de l'IBC."

Keith Wallis, Surbiton, Surrey

(*) Contrairement à ce que Keith Wallis pense, Radio International, entendue sur l'émetteur de Fécamp, n'avait aucun lien avec la Société des émissions Radio Normandie qui avait suspendu toutes ses activités depuis le 7 septembre 1939, rappelons-le. L'émetteur de Fécamp était devenu la propriété de la SIT (Société Informations et Transmissions) de Max Brusset, homme trouble et opportuniste en cheville avec l'IBC. Celui-ci pour se venger de son ex-"patron" Fernand Le Grand (qui l'avait "viré" à la suite de diverses trahisons), envisageait de déménager le poste émetteur à Epône près de Paris pour concurrencer Radio Normandie. (Lire à ce sujet "L'histoire de la radio en France" de René Duval )

(**) Le livre "And the World listened" promis par Keith Wallis est finalement paru en février 2008. Voir le paragraphe 2008

Pour en savoir plus, cf notre chapitre sur :

RADIO INTERNATIONAL FECAMP |

Just before the publication of his book "And The World listened"

in 2008, Keith Wallis had written an article in the magazine "Best of British" in February 2000...

The first broadcasts in

English from the continent

Note: remember that in Great Britain, advertising is prohibited on the BBC and commercial radio stations were not authorized until 1973. In the 1930s, to circumvent the law, British advertisers simply had to rent time to antenna on commercial stations on the continent heard in the United Kingdom (Radio Luxembourg, Radio Normandie, Radio Toulouse...):

"Many European stations in the 1930s had their programs sponsored by the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) of London. The IBC was the creation of Captain L. Plugge who had earned that rank in the RAF. His first success with the 'IBC was Radio Fécamp which started its English programs on September 6, 1931. The first presenter was William Evelyn Kingwell, a cashier at a branch of the National Provincial Bank in Le Havre, who rode a motorcycle to Fécamp to play records Sunday evenings from 10:30 p.m. to 1 a.m. Three months later, it became Radio Normandy with Maxy Stanniford and Stephen Williams, first Saturday and Sunday and then finally every weekday from April 1933.

Radio Paris had existed since 1931 and continued its programs in English until the French had had enough of them at the end of 1933. Le Poste Parisien took over until 1939. The director of English programs on Radio Paris, Stephen Williams left for Luxembourg at the end of 1933. The IBC did not officially supply programs to Radio Luxembourg, as the station was engaged with its "Radio Publicity" advertising company in London, but that is another story. A completely different Radio Luxembourg came into existence after the war until its final closure in December 1991.

Radio Toulouse started in October 1931 with W. Brown-Constable as presenter. Tom Ronald replaced him in 1933 until English broadcasts were suspended in July of that year. These broadcasts resumed a little later in October 1937. Henry Hall is said to have been involved in this start-up.

As for other stations, there were plenty of them. Radio Côte d'Azur in Juan-les-Pins started in April 1934 becoming Radio Mediterranée in April 1937. Ljubliana, Athlone, Union Radio Madrid, San Sebastian, Barcelona, Valencia and Rome all carried out English broadcasts from time to time . Spain also had two short wave stations in Aranjuez and Madrid EAQ. Naturally, all of them closed on the declaration of war.

Radio Normandy continued for a while as Radio International to entertain the troops (*). Radio Normandy had inaugurated its new transmitter center in Louvetot in 1938 with great ceremony, with new studios in Caudebec-en-Caux. Unfortunately war was declared the following year and the Germans took possession of the installations. The castle of Louvetot survived, which is not the case of Radio Normandy, like antennas. But it was a church that bought the facilities.

Several celebrities started their careers at these stations, Roy Plomley, Bob Danvers-Walker (the voice of Pathé News during the war on newsreels!), Tom Ronald, Philipp Slessor and Jack Hargreaves to name just five. In 1939, the International Broadcasting Company must stop but it opens again after the war as very famous recording studios. Captain L. Plugge lost much of his investment (!) in the adventure except for the low income he received as a member of the British Parliament. He had been elected Conservative MP for Colchester in 1935.

The full story of these 1930s radio stations is told in the biography I wrote about Captain L. Plugge entitled "And the world listened"** which I will publish ... if a publisher devotes himself! An appendix gives full dates and other details of all IBC stations."

Keith Wallis, Surbiton, Surrey

(*) Contrary to what Keith Wallis thinks, Radio International, heard on the Fécamp transmitter, had no connection with the Société des Emissions Radio Normandie which had suspended all its activities since September 7, 1939, let us remember. The Fécamp transmitter had become the property of the SIT (Information and Transmission Company) of Max Brusset, a troubled and opportunistic man in close contact with the IBC. The latter, to take revenge on his ex-"boss" Fernand Le Grand (who had "fired" him following various betrayals), planned to move the transmitter station to Epône near Paris to compete with Radio Normandie.

(**) The book "And the World listened" promised by Keith Wallis was finally published in February 2008. See the 2008 paragraph

To learn more, see our chapter on :

RADIO INTERNATIONAL FECAMP |

|

2002

|

|

A Concise History A Concise History

of British Radio

par Sean Street - 2002 - Kelly Publications

Sean Street, broadcaster, poet and historian, is Professor of Radio in the Bournemouth Media School at Bournemouth University, the first person to hold such a post in this country. Issued as a companion volume to Tony Currie's A CONCISE HISTORY OF BRITISH TELEVISION this informative and entertaining book is a completely original publication. Sean Street, broadcaster, poet and historian, is Professor of Radio in the Bournemouth Media School at Bournemouth University, the first person to hold such a post in this country. Issued as a companion volume to Tony Currie's A CONCISE HISTORY OF BRITISH TELEVISION this informative and entertaining book is a completely original publication.

To quote from Piers Plowright's Preface it is: "a coherent and dramatic sweep from the first scientifically-based attempts to send sound messages over distance to the rich and sometimes rude complexity of 21st century digital broadcasting...The style is crisp, clear and often witty." Perhaps uniquely in a study of radio history this excellent book recognises the importance of the various commercial radio stations, pre-war as well as post-war, balanced against those of the BBC

|

Livre en anglais à découvrir ici > https://www.worldradiohistory.com/UK/UK-Books/A-Concise-History-of-British-Radio-1922-2002-Street-2002.pdf#search=%22fernand%20le%20grand%22 Livre en anglais à découvrir ici > https://www.worldradiohistory.com/UK/UK-Books/A-Concise-History-of-British-Radio-1922-2002-Street-2002.pdf#search=%22fernand%20le%20grand%22

"Une histoire concise de la radio britannique" par Sean Street - 2002 - Kelly Publications

Sean Street, radiodiffuseur, poète et historien, est professeur de radio à la Bournemouth Media School de l'université de Bournemouth, la première personne à occuper un tel poste dans ce pays. Publié en complément de A CONCISE HISTORY OF BRITISH TELEVISION de Tony Currie, ce livre informatif et divertissant est une publication totalement originale.

Pour citer la préface de Piers Plowright, il s'agit : "Un inventaire cohérent et spectaculaire depuis les premières tentatives scientifiques d'envoyer des messages sonores à distance jusqu'à la complexité riche et parfois grossière de la radiodiffusion numérique du XXIe siècle... Le style est vif, clair et souvent spirituel. Cet excellent ouvrage est peut-être le seul à reconnaître l'importance des diverses stations de radio commerciales, d'avant-guerre et d'après-guerre, par rapport à celles de la BBC.

|

2003

|

Radio Normandy Radio Normandy

the station that shook the BBC

by Eric Westman (with grateful acknowledgements

to M. J-P Durand-Chédru of Fécamp)

Radio Normandie la station qui a fait

trembler la BBC

Un article de 6 pages paru dans le British Vintage Wireless Society BVWS Bulletin 28-1 (Spring 2003)

https://www.bvws.org.uk/publications/bulletins/pdf/BVWS_Bulletin_28_1.pdf

|

The first two pages / Les deux premières pages...

> BVWS pdf - (english pages)

> pages traduites en français (recomposées à l'identique au format pdf)

|

|

2006

|

|

Traverser l'éther (l'espace hertzien) Traverser l'éther (l'espace hertzien)

par Sean Street - 2006 -

Indiana University Press

Tout laisse croire que le monopole de la BBC n'a jamais été sérieusement remis en cause avant l'avènement d'ITV en 1955. "Crossing the Ether" contredit ce point de vue et raconte le premier défi de la radio commerciale auquel le monopole du service public a été confronté durant les années 1930 à 1939. La radio en Grande-Bretagne était un champ de bataille entre les stations continentales, dirigées par des intérêts commerciaux britanniques ou américains, et la BBC assaillie par ses principes paternalistes et sabbataires.

Histories of British broadcasting suggest that the BBC monopoly was never seriously challenged until the coming of ITV in 1955. "Crossing the Ether" counters this view, telling the story of commercial radio's first challenge to the Public Service monopoly between 1930 and 1939. In the telling, this account provides substantial primary evidence that radio in Britain during the 1930s was a battleground between continental-based stations, run by British and American commercial interests, and the BBC, beset by paternalistic and sabbatarian principles.

> le texte français (seuls les 2 chapitres sur Radio Normandie)

> text pdf english - (Pages Radio Normandy > 265 and 321)

|

|

2008

|

Lenny Plugge créa l'IBC - L'International Broadcasting Company - en 1930. Le siège de la compagnie était situé au 11 Hallam Street dans le centre de Londres à quelques mètres des studios de la BBC.

En contournant le monopole de la BBC qui interdisait toute forme de publicité sur les ondes, L. Plugge a contribué au développement de la radio commerciale au Royaume Uni, en utilisant les stations basées sur le continent européen, Radio Paris, le Poste Parisien et surtout Radio Normandie. La réussite de ses activités radiophoniques a fait sa fortune. En revanche, sa vie personnelle a été nettement moins brillante.

Ce livre raconte sa vie complète : ses voyages d'affaires à travers l'Europe des années 20 dans des voitures équipées d'énormes postes radiotéléphone et antennes-cadres, le développement de l'IBC, dix années de politicien en tant que membre du Parlement, un mariage raté et des tragédies familiales à la fin de sa vie.

On y retrouve les noms de personnages célèbres qu'il a croisés : Jacqueline Bouvier (la future Jacky Kennedy), Lady Docker, Annigoni, Sarah Churchill, Noel Coward, Hugh Gaitskill, Mick Jagger (Rolling Stones), April Ashley et Michael X. |

| Lenny Plugge founded the IBC - the International Broadcasting Company - in 1930. The company's headquarters were located at 11 Hallam Street in central London, a few yards from the BBC studios.

By circumventing the BBC's monopoly against advertising on the airwaves, L. Plugge contributed to the development of commercial radio in the UK, using stations based on the European continent, Radio Paris, Le Poste Parisien and especially Radio Normandie. The success of his radio activities made his fortune. His personal life, however, was far less successful.