|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

Radio-Pictorial Radio-Pictorial

|

Radio-International2 Radio-International2 |

|

Historical website in French and English Historical website in French and English

La brève histoire d'une radio méconnue

The brief history of an unknown radio...

IMPORTANT Sans relation avec l'ancienne société "Emissions Radio Normandie"

Unrelated to the former Company "Emissions Radio Normandie" Unrelated to the former Company "Emissions Radio Normandie"

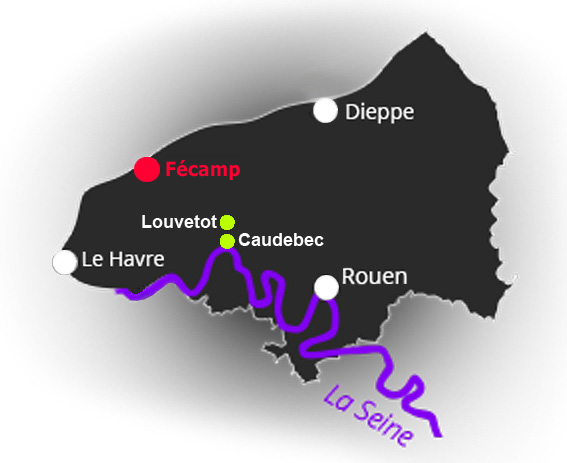

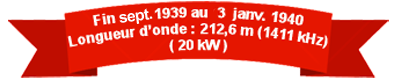

RADIO INTERNATIONAL FeCAMP - 212,6 m

De fin septembre 1939 jusqu'au mercredi 3 janvier 1940

From the end of September 1939 until Wednesday, January 3, 1940

|

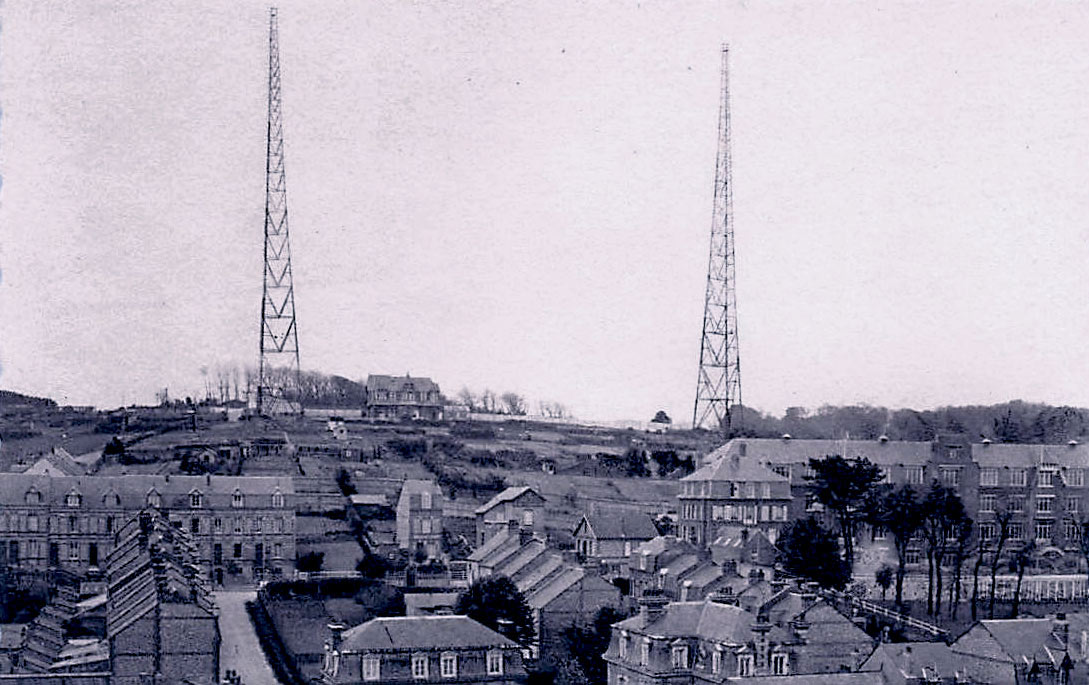

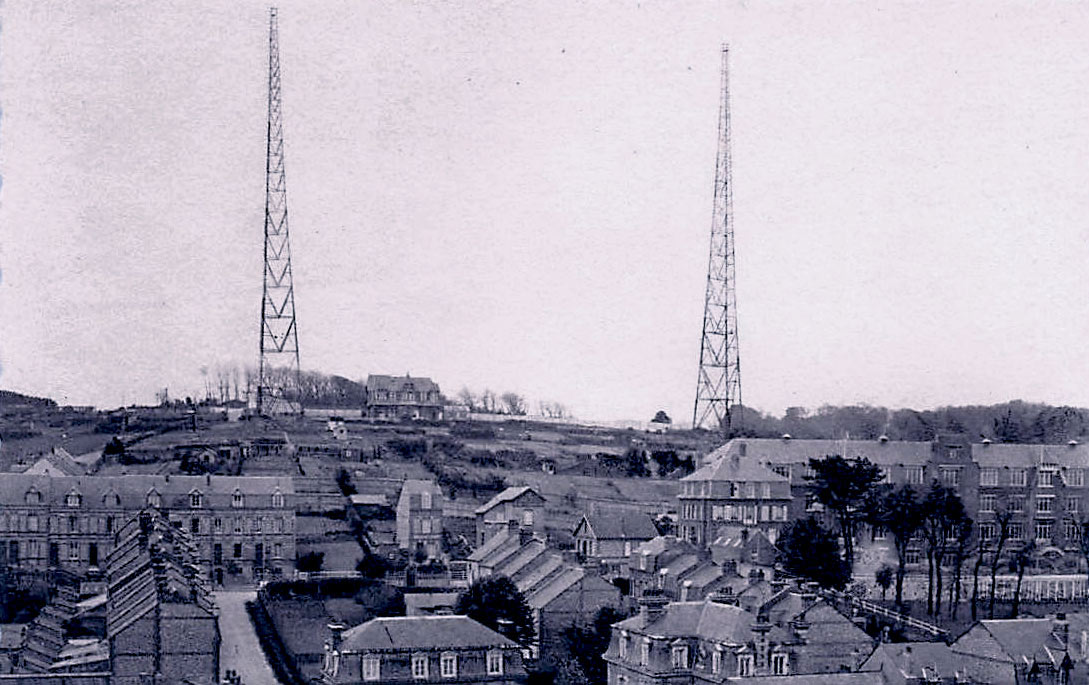

Janvier 1940 à Fécamp : voici la cheminée fumante de la distillerie de la Bénédictine. On aperçoit l'une des deux antennes,

celle côté est de la station de radio.

January 1940 in Fécamp : here is the smoking chimney of the Bénédictine distillery. We can see one of the two antennas,

the one on the east side of the radio station.

|

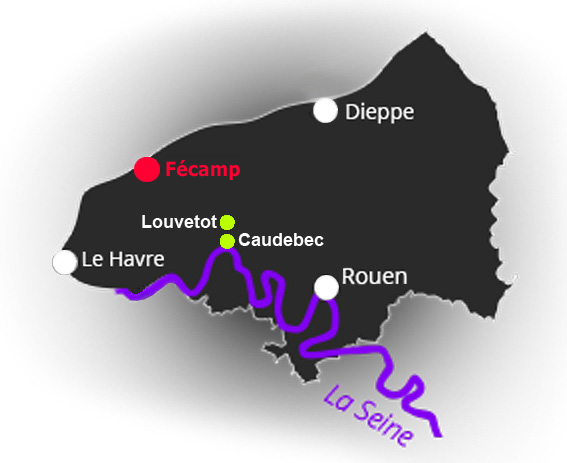

RADIO INTERNATIONAL FECAMP

Après la fermeture de Radio Normandie en 1939 (à Louvetot), l'IBC a donc utilisé ses ressources et l'ancien émetteur de Fécamp remis en service, sans le soutien de la publicité pour créer des programmes pour les forces expéditionnaires britanniques en France jusqu'à sa fermeture par une décision conjointe des gouvernements britannique et français le 3 janvier 1940.

Sean Street - extrait de son livre "British Radio" |

RADIO INTERNATIONAL FECAMP

After the closure of Radio Normandy (Louvetot) in 1939, the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) used its ressources and transmitter (Fecamp) without the support of sponsorship by advertising to create programs for the british expeditionary forces in France until it was closed down by a joint british and french government ruling on 3 January 1940.

Sean Street - from "British Radio" |

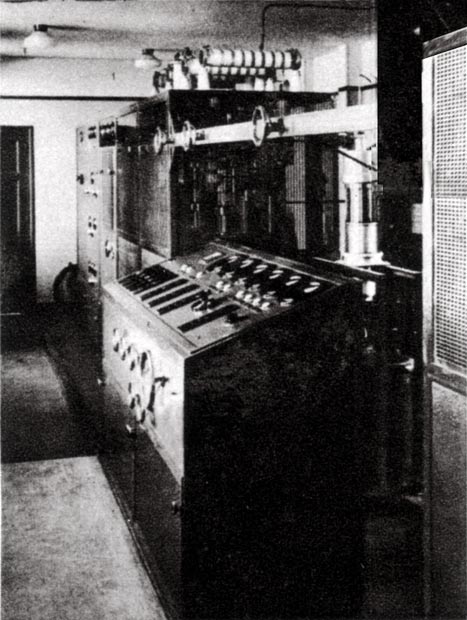

L'ancien émetteur de Fécamp à l'arrêt depuis le transfert le 12.12.1938 de Radio Normandie à Louvetot, reprend du service un an plus tard, fin septembre 1939, sous le nom de Radio International pour quelques semaines seulement sous le contrôle de l'IBC. L'ancien émetteur de Fécamp à l'arrêt depuis le transfert le 12.12.1938 de Radio Normandie à Louvetot, reprend du service un an plus tard, fin septembre 1939, sous le nom de Radio International pour quelques semaines seulement sous le contrôle de l'IBC.

En septembre 1939, l’idée de créer une « Radio International » est planifiée par l’International Broadcasting Company (IBC) pour diffuser en langue anglaise des programmes de divertissement destinés aux forces armées basées en Europe en utilisant les anciennes facilités de « Radio Normandy » à Fécamp. Baptisée « comme la radio de derrière les lignes », la station serait sur les ondes de 7 h à 18 h 00. Les émissions seraient enregistrées sans messages publicitaires.

La station de l’IBC à Fécamp commence donc ses émissions fin septembre – début octobre, jouant des disques de musique légère ou musique de danse pendant la journée jusqu’à 19 h 15. Tous les quarts d’heure, on entend le vieux carillon de « Radio Normandy » suivi de l’annonce « This is the International Broadcasting Station, preparing a new service ». La station de l’IBC à Fécamp commence donc ses émissions fin septembre – début octobre, jouant des disques de musique légère ou musique de danse pendant la journée jusqu’à 19 h 15. Tous les quarts d’heure, on entend le vieux carillon de « Radio Normandy » suivi de l’annonce « This is the International Broadcasting Station, preparing a new service ».

Incapables de pouvoir se fournir en programmes depuis Londres ou de pouvoir en recevoir une quantité suffisante, des enregistrements sont importés des États-unis. Bob Danvers Walker est nommé chef annonceur et lecteur d’informations. Il n’y a pas de publicité à cause de l’état de guerre. Seul le nom du sponsor est indiqué au début et à la fin de l’enregistrement, probablement ajouté au dernier moment à la station.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The former Fécamp transmitter, which had been turned off since the transfer of Radio Normandie to Louvetot on 12.12.1938, resumed service at the end of september 1939 under the name of Radio International for only a few weeks (from Nov. 1939 to Friday, Jan. 12, 1940) under the control of the IBC. The former Fécamp transmitter, which had been turned off since the transfer of Radio Normandie to Louvetot on 12.12.1938, resumed service at the end of september 1939 under the name of Radio International for only a few weeks (from Nov. 1939 to Friday, Jan. 12, 1940) under the control of the IBC.

In September 1939, the idea of creating an "International Radio" was planned by the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) to broadcast English-language entertainment programs for the armed forces based in Europe using the former facilities of " Radio Normandy” in Fécamp. Dubbed “like radio from behind the lines,” the station would be on the air from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. The broadcasts would be recorded without commercial messages.

The IBC station in Fécamp therefore begins its broadcasts again at the end of September – beginning of October, playing discs of light music or dance music during the day until 7:15 p.m. Every quarter of an hour, we hear the old carillon of “Radio Normandy” followed by the announcement “This is the International Broadcasting Station, preparing a new service”.

Unable to obtain programs from London or to receive a sufficient quantity, recordings were imported from the United States. Bob Danvers Walker is named chief announcer and newsreader. There is no advertising because of the state of war. Only the name of the sponsor is indicated at the beginning and end of the recording, probably added at the last moment at the station. |

|

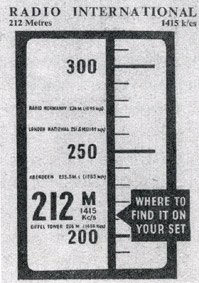

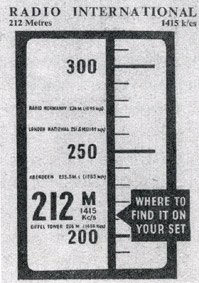

RADIO INTERNATIONAL "la station derrière les lignes"

depuis l'ancien émetteur de Radio Normandie à Fécamp sur 212 m

RADIO INTERNATIONAL "the station behind the lines"

from the old Radio Normandie transmitter in Fécamp on 212 m

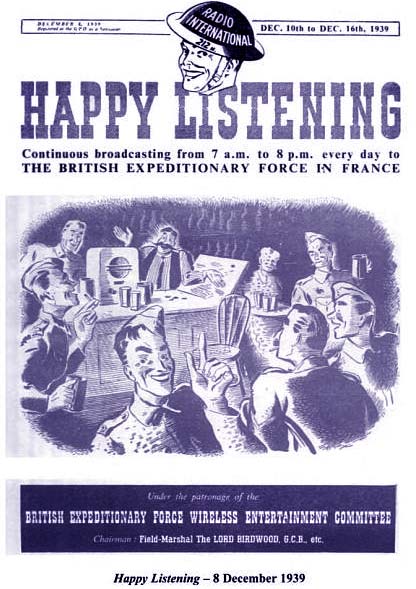

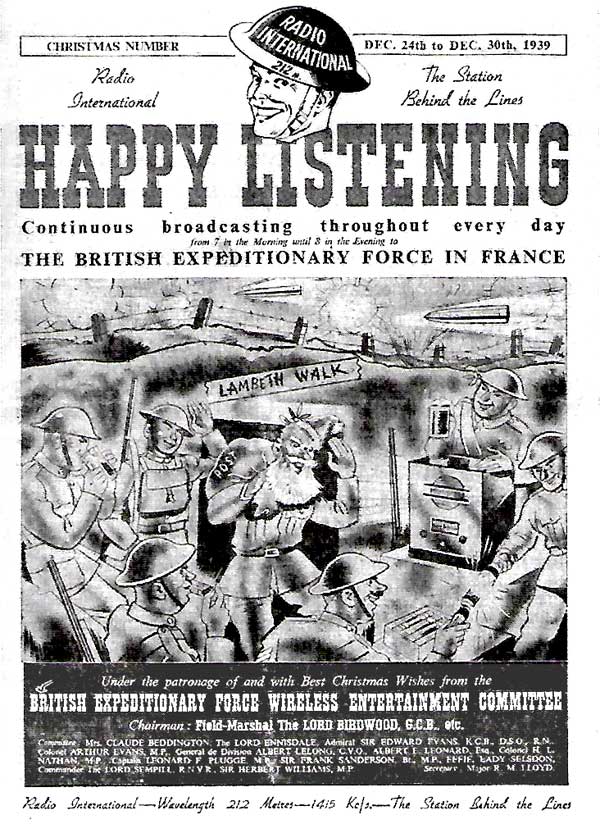

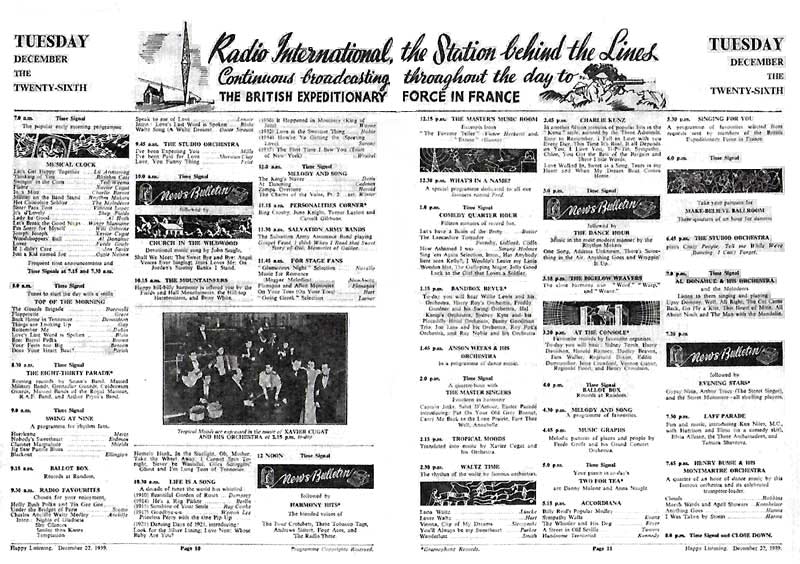

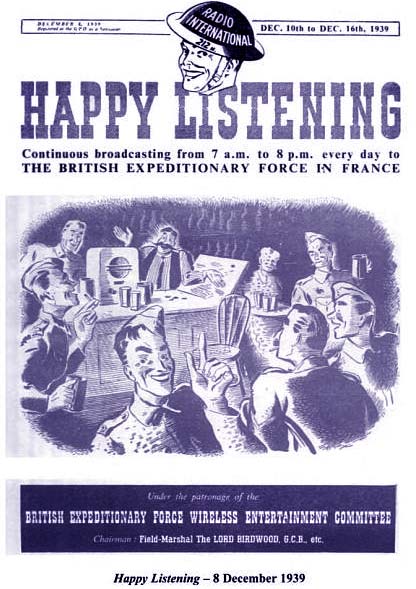

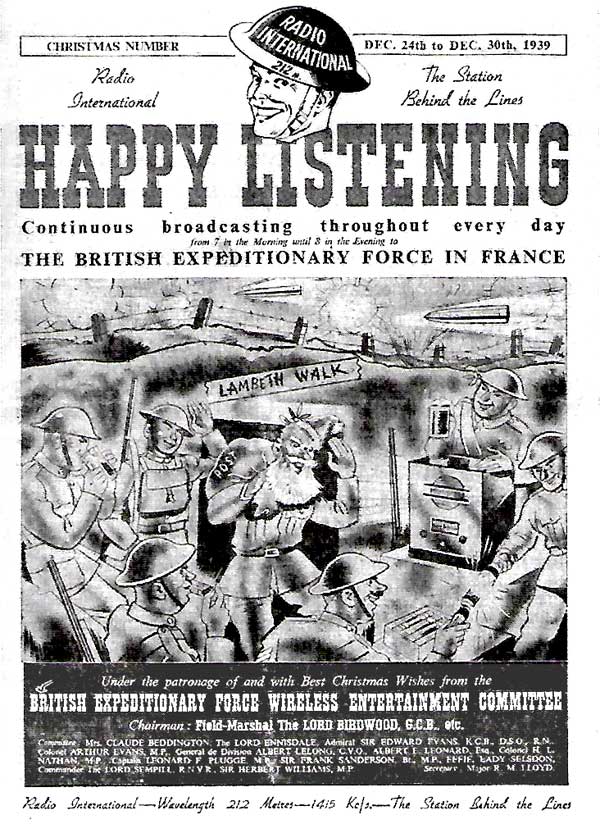

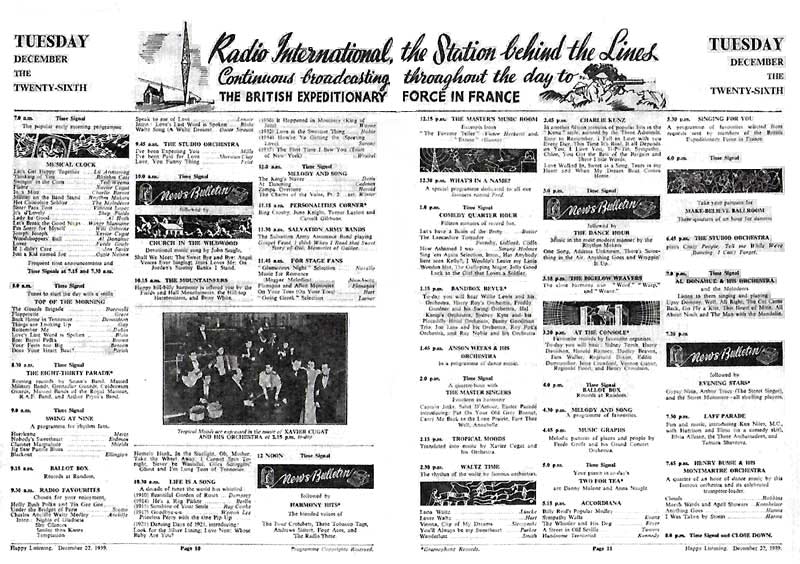

L'IBC a produit une nouvelle feuille d'écoute Happy Listening (parution de deux numéros seulement) portant

sur chaque page le titre : "Radio International : Broadcasting to the British Expeditionary Force in France".

Le titre de la feuille était clairement destiné à assurer une continuité dans l'esprit

des auditeurs britanniques avec

la défunte Radio Normandie

The IBC produced a new "Happy Listening" sheet (only two issues

published) bearing the title "Radio International:

Broadcasting to the British Expeditionary Force in France" on each page. The

sheet's title was clearly intended

to ensure continuity in the minds of British listeners with the now-defunct

Radio Normandie.

|

Aperçu des programmes édité par l'IBC (cliquer pour agrandir - click for enlarge)

|

< Fin septembre 1939 jusqu'au 3 janvier 1940,

les antennes de Fécamp reprennent du service

sur la vieille longueur d'onde de 212,6 m

End of September 1939 to 3 January 1940,

the antennas of Fécamp resume service

on the old wavelength of 212.6 m

|

Fin 1939, le morceau orchestré "Keep the home fires burning" - à entendre ici : Fin 1939, le morceau orchestré "Keep the home fires burning" - à entendre ici :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-b4hoQ_XYos&ab_channel=JohnMcCormack-Topic

est utilisé comme indicatif de fin de "Radio International Fécamp". L'IBC a été chargée des émissions en anglais destinées aux forces britanniques basées en France mais avec des programmes intégralement américains (les studios de Londres ne pouvaient plus fournir d'émissions), beaucoup de disques, les nouvelles de l'Agence Havas lues par Bob Danvers-Walker. Les émissions (sans publicité) s'arrêtaient après les infos de 19 heures.

At the end of 1939, the orchestrated piece "Keep the home fires burning" :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-b4hoQ_XYos&ab_channel=JohnMcCormack-Topic

is used as the end sign of "Radio International Fécamp". The IBC was in charge of the broadcasts in English intended for the British forces based in France but with all-American programs (the London studios could no longer provide broadcasts), many records, the Havas news read by Bob Danvers-Walker. The broadcasts (without commercials) stopped after the 7 p.m. news.

|

| |

Le projet de Radio International Fécamp

Après la déclaration de guerre de l'Angleterre et de la France contre l'Allemagne nazie et la réquisition de Louvetot le 8 septembre 1939, le Captain Plugge devenu conseiller auprès du Comité de divertissement de la Force expéditionnaire britannique, persistait dans son intention de créer un programme de radio destiné aux troupes britanniques. Il fournit au Comité des tableaux comparatifs de contenu de programmes, montrant comment l'IBC avait l'intention d'utiliser l'émetteur disponible de Fécamp. Cet émetteur avait été racheté par la S.I.T.

(Société Informations et Transmissions appartenant à Max Brusset) Un programme au nom de “Radio International” serait mis en compétition avec celui de la BBC qui est très populaire auprès des soldats. Il serait composé de 91 % de musique, 8 % d'informations et 1 % réservé aux sponsors. Le terme “sponsor” ne serait utilisé en aucun cas. Plugge voulait que les troupes puissent écouter le genre de programmes qu'elles méritent. Fécamp devait être animé par les annonceurs de l'IBC : Bob Danvers-Walker, Philip Slessor et Charles Maxwell. George Busby était le manager. Il était prévu que les Tchèques et les Autrichiens libres participeraient également aux émissions. Les sponsors habituels avaient été approchés au Royaume-Uni pour leur demander l’approbation de diffuser leurs anciens programmes d'avant-guerre. Les émissions devraient commencer à 7.00 et se poursuivre jusqu'à 18.00 ; les Autrichiens et les Tchèques prendraient ensuite le relais avec deux heures dans chaque langue.

Il restait quelques difficultés à résoudre. Un règlement stipulait que toutes les transmissions devaient être interrompues dès qu'une sirène d'alerte aérienne retentissait. Malheureusement pour Radio International, la sirène locale située sur le toit de la Bénédictine juste à côté, semblait retentir plus souvent que nécessaire. Par mesure de sécurité, les stations de radio devaient être synchronisées (sur une même longueur d’onde) afin d’éviter que les avions ennemis n'utilisent une station isolée comme balise de repérage. Fécamp n'était pas synchronisée et pour cette raison, les gouvernements britannique et français tentèrent à plusieurs reprises de faire fermer la station. Cependant, personne ne pouvait déterminer qui était responsable de Fécamp. Par conséquent la station continua de fonctionner.

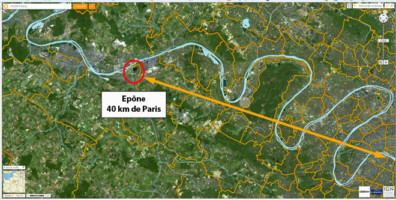

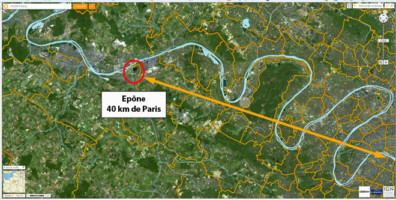

Radio International à Epone

(Seine et Oise)

George Shanks, avec l'approbation de Plugge, organisa l'achat d’un château du XVIIe siècle dans la petite ville d'Epone, près de Mantes, à 40 kilomètres à l'ouest de Paris. L'intention était d'installer une seconde station, surmontant ainsi les objections concernant l'absence de station "reliée" à Fécamp. Obtenir du matériel et de l'équipement à cette époque était difficile et les travaux au château progressaient lentement. George Shanks s'efforça de résoudre les problèmes au fur et à mesure qu'ils survenaient. Il mena les négociations avec les autorités françaises. Son contact politique était Max Brusset, chef de cabinet de Georges Mandel, ministre des PTT. Plugge connaissait Brusset et appréciait sa position au sein du gouvernement français. Il s'arrangea pour qu'il prenne les intérêts de l'IBC en France pendant l'occupation, avec l'idée qu'une station française ne pourrait être réquisitionnée par les Allemands. C'est dans cet esprit que la propriété de la nouvelle station d'Epone fut mise au nom de Brusset. Celui-ci possédait déjà des intérêts dans la radiodiffusion : il était propriétaire de la station Radio Méditerranée depuis 1937 qui sera détruite plus tard par les nazis(1).

(1) Max Brusset était aussi un ancien administrateur de la Société des Emissions Radio Normandie qui avait été évincé par Fernand Le Grand, celui-ci ayant découvert le double-jeu que Brusset menait dans son dos avec l’IBC. De plus M. Le Grand était persuadé que la réquisition de Louvetot (le seul poste français à être réquisitionné pour les "besoins de la défense nationale") était due à Max Brusset en représailles de son éviction. (cf livre de René Duval)

En novembre 1939, Roy Plomley arrivait à Fécamp pour remplacer Philip Slessor qui demandait à rentrer en Angleterre ne supportant plus le stress trop important. David Davies, Ralph Hurcombe, Maurice Griffith, Godfrey Holloway et George Busby devaient assister à des réunions hebdomadaires à Paris avec George Shanks et le ministère des Affaires étrangères pour discuter de l'avenir

du nouvel émetteur. Peu de temps après son arrivée, Roy Plomley était invité à les rejoindre. L’idée était de mettre en place un programme hebdomadaire destiné à l’instruction des troupes britanniques sur les coutumes françaises et l’apprentissage de quelques mots et phrases utiles. Le programme appelé “La demi-heure du Tommy”, fut confié à Roy avec l’assistance de conseillers titrés et cultivés. L’enregistrement s’effectuerait chaque semaine dans les studios du Poste Parisien

(à Paris) pour être diffusé depuis Fécamp. Puis la demi-heure est réduite au "Quart d'heure du Tommy". La station a commencé ses émissions fin septembre 1939 sous le nom de "Radio International". Cela a aussitôt donné lieu à une série de correspondances, classées secrètes, entre diverses autorités en Angleterre. Alors que le ministère de l'Air voulait fermer la radio parce qu'elle ne faisait pas partie d'un groupe de stations synchronisées et pouvait être utilisée comme balise par les avions ennemis, le GPO (Ministère britannique des Postes) et la BBC avaient leurs propres raisons de souhaiter la fermeture de Fécamp, certains affirmaient que la BBC fournirait un meilleur service, alors que d'autres pensaient que Fécamp faisait un bon travail. Cependant, la valeur du divertissement fut jugée négligeable par rapport au préjudice causé pour la sécurité. En conséquence, la fermeture définitive de Fécamp fut ordonnée le 3 janvier 1940 par les autorités françaises. La mélodie de clôture de Radio International

“Keep the Home Fires Burning d'Ivor Novello” était entendue pour la dernière fois. du nouvel émetteur. Peu de temps après son arrivée, Roy Plomley était invité à les rejoindre. L’idée était de mettre en place un programme hebdomadaire destiné à l’instruction des troupes britanniques sur les coutumes françaises et l’apprentissage de quelques mots et phrases utiles. Le programme appelé “La demi-heure du Tommy”, fut confié à Roy avec l’assistance de conseillers titrés et cultivés. L’enregistrement s’effectuerait chaque semaine dans les studios du Poste Parisien

(à Paris) pour être diffusé depuis Fécamp. Puis la demi-heure est réduite au "Quart d'heure du Tommy". La station a commencé ses émissions fin septembre 1939 sous le nom de "Radio International". Cela a aussitôt donné lieu à une série de correspondances, classées secrètes, entre diverses autorités en Angleterre. Alors que le ministère de l'Air voulait fermer la radio parce qu'elle ne faisait pas partie d'un groupe de stations synchronisées et pouvait être utilisée comme balise par les avions ennemis, le GPO (Ministère britannique des Postes) et la BBC avaient leurs propres raisons de souhaiter la fermeture de Fécamp, certains affirmaient que la BBC fournirait un meilleur service, alors que d'autres pensaient que Fécamp faisait un bon travail. Cependant, la valeur du divertissement fut jugée négligeable par rapport au préjudice causé pour la sécurité. En conséquence, la fermeture définitive de Fécamp fut ordonnée le 3 janvier 1940 par les autorités françaises. La mélodie de clôture de Radio International

“Keep the Home Fires Burning d'Ivor Novello” était entendue pour la dernière fois.

L’IBC cesse son activité

Le dernier souffle de l’IBC a lieu au printemps 1940 quand le Poste Parisien et probablement la station de Fécamp retransmettent pendant quelques samedis après-midi « Le quart d’heure du Tommy » composé de disques sans annonces.

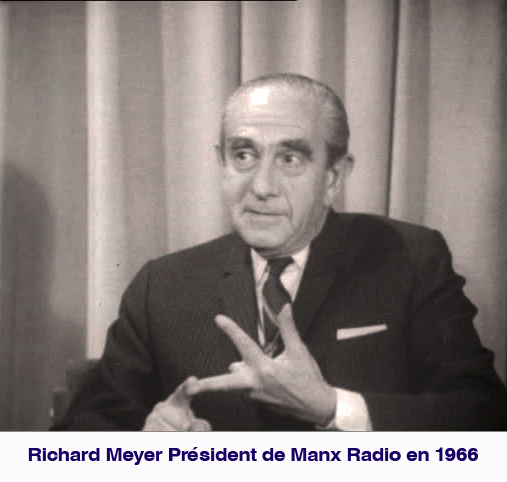

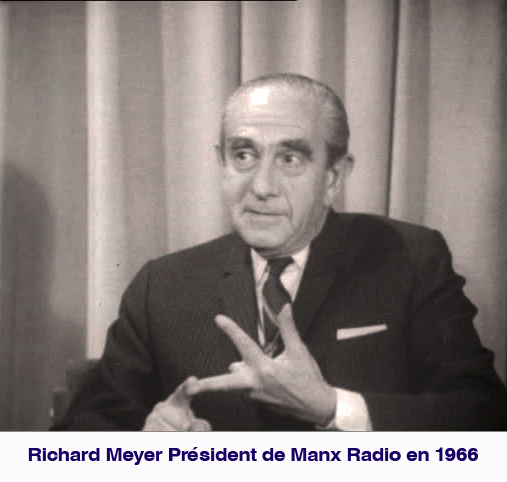

Tous les membres de l’IBC ont été réunis à Fécamp en présence de Richard Meyer directeur de l’IBC qui a annoncé qu'il ne fallait espérer aucun emploi futur avec l'IBC et qu’ils devaient prendre leurs dispositions. Bob Danvers-Walker est retourné à Londres et a obtenu un emploi aux Actualités Pathé. D'autres, comme Charles Maxwell et Tom Ronald sont entrés à la BBC.

En juin 1940, alors que les Allemands sont proches de Paris, Epone est alors aux mains de Brusset. Malgré la propriété française, les nazis réquisitionnent le studio pour transmettre leur propagande sous le nom de "Radio Calais" vers le Royaume-Uni. Entre-temps Roy Plomley était retourné à Paris dans le vain espoir que le Poste Parisien pourrait reprendre ses émissions. Il avait du mal à croire que Paris allait tomber, mais c'est ce qui s'est passé. Lui et sa femme Diana ont réussi à quitter la France au dernier moment, échappant de justesse aux arrestations.

Le 10 juin 1940 à Fécamp, alors que les forces allemandes approchaient, l'armée française coupait les câbles reliant l'émetteur aux antennes. Mais les Allemands se sont emparés des anciens studios de Fécamp pour installer leur Kommandantur, signifiant la fin définitive de Radio Normandie.

L'un des pylônes d'antenne sera détruit lors d'une violente tempête le 7 novembre 1940. L'autre sera dynamité par les Allemands le 12 novembre 1943 afin de supprimer un possible point de repère pour les forces alliées. Quant au Château d'Epone, en 1944, les Allemands étaient en retraite alors que les troupes américaines avançaient. Le studio et les émetteurs furent détruits ; les troupes alliées arrivèrent le lendemain. Max Brusset et sa femme Marie, membres actifs de la Résistance, avaient été arrêtés et condamnés à mort. Heureusement, ils furent libérés à temps par les troupes américaines. Par la suite, Max Brusset devint maire de Royan et servit dans le gouvernement jusqu'en 1958. Il resta propriétaire du château d'Epone, bien que Plugge ait toujours prétendu qu'il lui appartenait de droit.

D'après "And the World listened" by Keith Wallis |

The Radio International Fecamp Project

After the declaration of war by England and France against Nazi Germany and the requisition of Louvetot on 8 September 1939, Captain Plugge, who had become an advisor to the Entertainment Committee of the British Expeditionary Force, persisted in his intention to create a radio programme for the British troops. He provided the Committee with comparative tables of programme content, showing how the IBC intended to use the available transmitter at Fécamp. This transmitter had been bought by S.I.T. (Société Informations et Transmissions owned by Max Brusset). A programme called “Radio International” would be put in competition with that of the BBC which was very popular with the soldiers. It would consist of 91% music, 8% news and 1% reserved for sponsors. The term “sponsor” would not be used under any circumstances. Plugge wanted the troops to be able to listen to the kind of programmes they deserved. Fécamp was to be hosted by the IBC announcers Bob Danvers-Walker, Philip Slessor and Charles Maxwell. George Busby was the manager. It was planned that the Czechs and the Free Austrians would also take part in the broadcasts. The usual sponsors had been approached in the UK to ask for permission to broadcast their old pre-war programmes. The broadcasts were to start at 7.00 and continue until 18.00, with the Austrians and Czechs taking over with two hours in each language.

There were still some difficulties to be resolved. A regulation stipulated that all transmissions had to be interrupted as soon as an air raid siren sounded. Unfortunately for Radio International, the local siren on the roof of the Benedictine next door seemed to sound more often than necessary. As a safety measure, radio stations had to be synchronised (on the same wavelength) to prevent enemy aircraft from using an isolated station as a homing beacon. Fécamp was not synchronised and for this reason the British and French governments made several attempts to have the station closed down. However, no one could determine who was responsible for Fécamp. Consequently the station continued to operate.

Radio International at Epone

George Shanks, with Plugge's approval, arranged for the purchase of a 17th century chateau in the small town of Epone, near Mantes, 25 miles west of Paris. The intention was to set up a second station, overcoming objections about the lack of a "linked" station at Fécamp. Obtaining materials and equipment at this time was difficult and work on the chateau progressed slowly. George Shanks endeavoured to resolve problems as they arose. He led the negotiations with the French authorities. His political contact was Max Brusset, chief of staff of Georges Mandel, Minister of Post, Telephone and Telegraph. Plugge knew Brusset and appreciated his position within the French government. He arranged for him to take over the interests of the IBC in France during the occupation, with the idea that a French station could not be requisitioned by the Germans. It was with this in mind that the ownership of the new Epone station was put in Brusset's name. He already had interests in broadcasting: he had owned the Radio Méditerranée station since 1937, which would later be destroyed by the Nazis(1).

(1) Max Brusset was also a former administrator of the Société des Emissions Radio Normandie who had been ousted by Fernand Le Grand, who had discovered the double-dealing that Brusset was playing behind his back with the IBC. Furthermore, Mr. Le Grand was convinced that the requisition of Louvetot (the only French post to be requisitioned for the "needs of national defense") was due to Max Brusset in retaliation for his ouster. (cf. book by René Duval)

In November 1939, Roy Plomley arrived in Fécamp to replace Philip Slessor who had asked to return to England as he could no longer bear the stress. David Davies, Ralph Hurcombe, Maurice Griffith, Godfrey Holloway and George Busby were to attend weekly meetings in Paris with George Shanks and the Foreign Office to discuss the future of the new transmitter. Shortly after his arrival, Roy Plomley was invited to join them. The idea was to set up a weekly programme to instruct British troops in French customs and to teach them a few useful words and phrases. The programme, called “The Tommy's half-hour”, was entrusted to Roy with the assistance of qualified and cultured advisers. The recording would be done each week in the studios of the Poste Parisien (< at Paris) and broadcast from Fécamp. Then the half-hour was reduced to the “Tommy' quarter-hour”. The station began broadcasting at the end of September 1939 under the name “Radio International”.

This immediately gave rise to a series of classified correspondence between various authorities in England. While the Air Ministry wanted to close the station because it was not part of a synchronised group of stations and could be used as a beacon by enemy aircraft, the GPO and the BBC had their own reasons for wanting Fécamp closed, some arguing that the BBC would provide a better service, while others thought that Fécamp was doing a good job. However, the entertainment value was deemed negligible compared to the harm to safety. As a result, the definitive closure of Fécamp was ordered on January 3, 1940 by the French authorities. The closing tune of Radio International's "Keep the Home Fires Burning by Ivor Novello" was heard for the last time.

The IBC ceases its activity

The last breath of the IBC took place in the spring of 1940 when the Poste Parisien and probably the Fécamp station retransmitted for a few Saturday afternoons "Tommy's quarter-hour" composed of records without announcements.

All the members of the IBC were gathered in Fécamp in the presence of Richard Meyer, director of the IBC, who announced that no future employment with the IBC was to be expected and that they should make their arrangements. Bob Danvers-Walker returned to London and got a job at Pathé News. Others, such as Charles Maxwell and Tom Ronald joined the BBC. All the members of the IBC were gathered in Fécamp in the presence of Richard Meyer, director of the IBC, who announced that no future employment with the IBC was to be expected and that they should make their arrangements. Bob Danvers-Walker returned to London and got a job at Pathé News. Others, such as Charles Maxwell and Tom Ronald joined the BBC.

In June 1940, when the Germans were close to Paris, Epone was then in the hands of Brusset. Despite French ownership, the Nazis requisitioned the studio to transmit their propaganda under the name of "Radio Calais" to the United Kingdom. In the meantime Roy Plomley had returned to Paris in the vain hope that the Poste Parisien would resume broadcasting. He found it hard to believe that Paris would fall, but it did. He and his wife Diana managed to leave France at the last moment, narrowly escaping arrest.

On 10 June 1940 in Fécamp, as German forces approached, the French army cut the cables connecting the transmitter to the antennas. But the Germans took over the old studios in Fécamp to set up their Kommandantur, signalling the definitive end of Radio Normandie.

One of the antenna towers was destroyed in a violent storm on 7 November 1940. The other was dynamited by the Germans on 12 November 1943 in order to remove a possible landmark for the Allied forces. As for the Château d'Epone, in 1944, the Germans were in retreat while the American troops were advancing. The studio and transmitters were destroyed; the Allied troops arrived the next day. Max Brusset and his wife Marie, active members of the Resistance, had been arrested and sentenced to death. Fortunately, they were freed in time by the American troops. Subsequently, Max Brusset became mayor of Royan and served in the government until 1958. He remained the owner of the Château d'Epone, although Plugge always claimed that it was his by right.

From "And the World listened" by Keith Wallis |

|

|

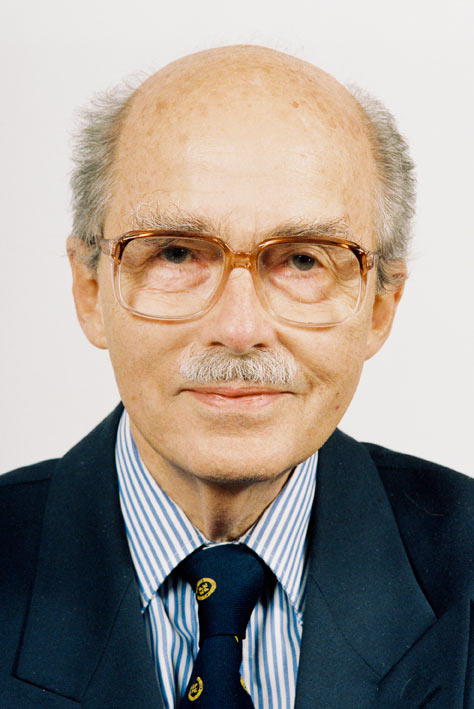

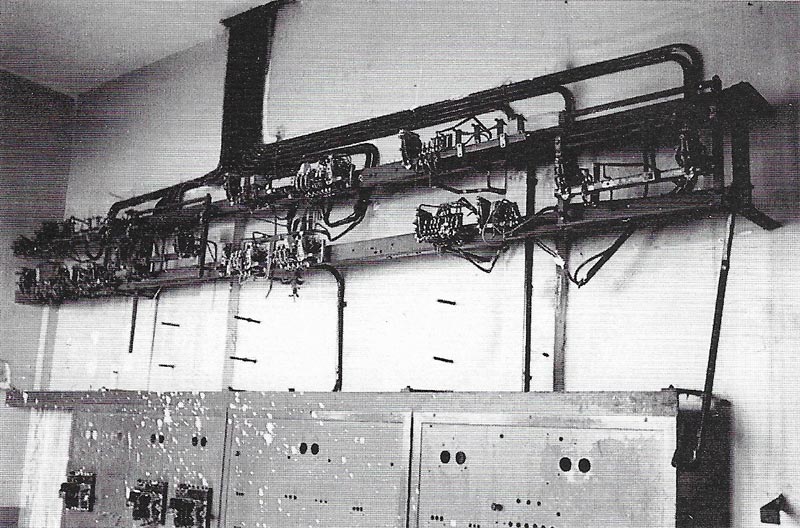

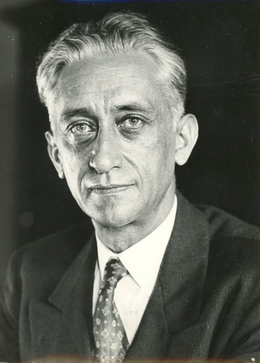

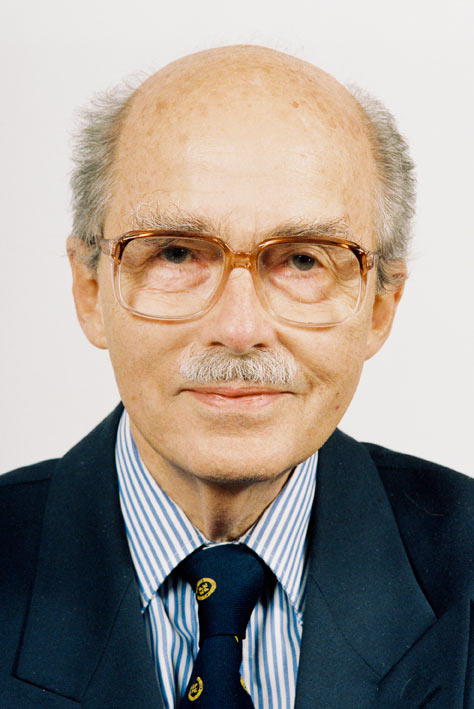

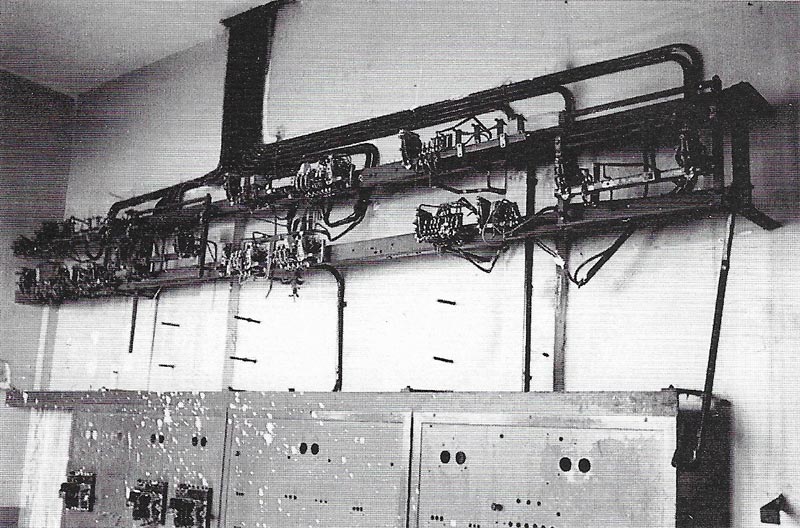

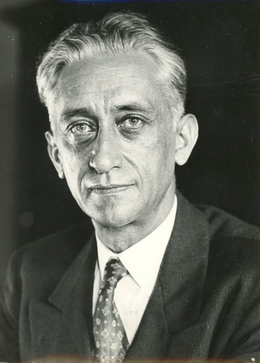

Les installations vacantes à Fécamp depuis le transfert à Louvetot le 12.12.1938

de Radio Normandie, avaient été rachetées par la S.I.T. (Société Informations et Transmissions) appartenant à un homme d'affaires opportuniste Max Brusset < photo

(ex-administrateur

de la Société Radio-Normandie, évincé du conseil par Fernand Le Grand) car Brusset avait conclu un accord en catimini avec l'IBC pour se venger de son ancien directeur. Les installations vacantes à Fécamp depuis le transfert à Louvetot le 12.12.1938

de Radio Normandie, avaient été rachetées par la S.I.T. (Société Informations et Transmissions) appartenant à un homme d'affaires opportuniste Max Brusset < photo

(ex-administrateur

de la Société Radio-Normandie, évincé du conseil par Fernand Le Grand) car Brusset avait conclu un accord en catimini avec l'IBC pour se venger de son ancien directeur.

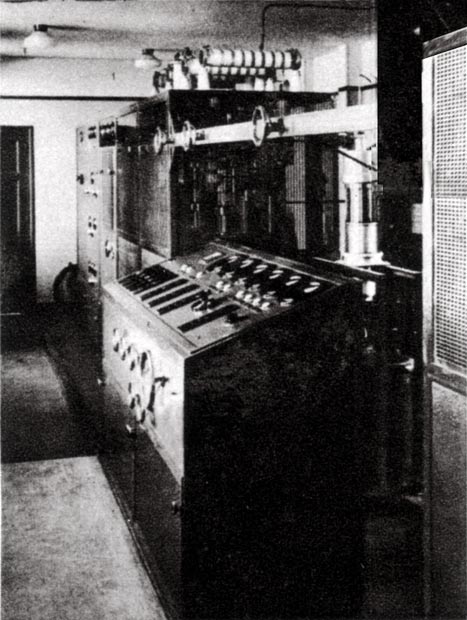

Fin septembre 1939 jusqu'au 3 janvier 1940 : des émissions en anglais commencent depuis l'ancien émetteur de Fécamp toujours opérationnel sur 212,6 m sous le nom "Radio International". Les émissions organisées par l'IBC consistent en programmes enregistrés sans mentionner les annonceurs publicitaires. Le slogan de la radio est "la station de derrière les lignes (ennemies)". Les émissions ont lieu de 7 à 18 h.

le poste diffuse des programmes pour les troupes britanniques engagées sur le continent.

Les émissions qui avaient pris pour titre « Le quart d’heure du  Tommy », étaient dirigées par l’ambassadeur Jacques Fouques-Duparc

< photo, et la comtesse Andrée de Fels. Dès le prélude de la guerre, fin juillet 1939, la société Radio-International avait acquis la propriété de l’ancien poste de Radio-Normandie installé sur la falaise de Fécamp dans un immeuble en bois, style chalet normand. A la demande du gouvernement français, sur l’initiative de M. Jean Mistler, président de la commission des Affaires étrangères à la Chambre des députés, l'émetteur prévoyait d'être transféré avec sa longueur d’ondes de 212,6 mètres, au poste dénommé, Radio-International (à Épone). Tommy », étaient dirigées par l’ambassadeur Jacques Fouques-Duparc

< photo, et la comtesse Andrée de Fels. Dès le prélude de la guerre, fin juillet 1939, la société Radio-International avait acquis la propriété de l’ancien poste de Radio-Normandie installé sur la falaise de Fécamp dans un immeuble en bois, style chalet normand. A la demande du gouvernement français, sur l’initiative de M. Jean Mistler, président de la commission des Affaires étrangères à la Chambre des députés, l'émetteur prévoyait d'être transféré avec sa longueur d’ondes de 212,6 mètres, au poste dénommé, Radio-International (à Épone).

Extrait du livre de René Duval : "Comme le moment est mal choisi pour lancer une station commerciale, l’émetteur de Fécamp de Max Brusset va servir, sous l’égide du commissariat général à l’information (Jean Giraudoux), du ministère des affaires étrangères (l’ambassadeur Fouques Du Parc), et de la commission des affaires étrangères de la chambre (Jean Mistler) à la propagande française en langue étrangère. Mais c’est la S.I.T. qui effectue toutes les démarches et qui paie, notamment, l’abonnement au service des dépêches de l’agence Havas

(Correspondance S.I.T.-Havas, d’octobre 1939 à janvier 1940. Archives Havas aux Archives nationales).

Les émissions en tchèque sont dirigées par MM. Mazarick et Osusky, celles en autrichien le sont par S.A. l’archiduc Otto de Habsbourg. Les archives ne permettent pas de déterminer le nom du rédacteur en chef des émissions polonaises.

Le deuxième acte de la pièce imaginée par Max Brusset — et dont il modifie l’intrigue au fur et à mesure des événements — consiste à faire transférer, pour raisons techniques de sécurité militaire, l’émetteur de 10 kW de Fécamp à Epône. La puissance en sera considérablement augmentée par l’adjonction de matériel Thomson-Houston spécialement commandé et le titre de la station : Radio-International-Fécamp sera changé pour celui de Radio-International-Epône. Là, les dirigeants de la fédération des postes privés commencent à se poser sérieusement des questions. Pour les calmer, Max Brusset écrit une longue lettre, le 9 mars 1940, à Jacques Tremoulet, vice-président de la fédération où il interdit à quiconque de mettre en doute sa parole et où il précise : L’installation du poste à Epône, dans la région parisienne, s’effectuera en accord et d’ordre du gouvernement dans un but d’intérêt général et de propagande française qu’il n’appartient à personne de discuter, et dont la réalisation ne saurait être attaquée. Ce poste n’émettra à aucun moment en langue française et ne fera aucune publicité commerciale française. Il est destiné uniquement à des émissions en langues étrangères, sous le contrôle du ministère des affaires étrangères et du commissariat général à l’information, à la disposition duquel il a été mis.

Très astucieusement, Max Brusset ne parle que de publicité française... il ne ment pas une seconde puisque si l’émetteur peut devenir commercial après les hostilités, il sera destiné à la publicité anglaise.

Mais l’arrivée des Allemands, en juin 1940, sonne le glas de ses belles espérances.". |

The vacant installations in

> Fécamp since the transfer to Louvetot on 12.12.1938 of Radio Normandie, had been bought by the S.I.T. (Société Informations et Transmissions) belonging to an opportunistic businessman Max Brusset

< photo (ex-administrator of the Société Radio-Normandie, ousted from the board by Fernand Le Grand) because Brusset had concluded an agreement on the sly with the IBC to take revenge on his former director. The vacant installations in

> Fécamp since the transfer to Louvetot on 12.12.1938 of Radio Normandie, had been bought by the S.I.T. (Société Informations et Transmissions) belonging to an opportunistic businessman Max Brusset

< photo (ex-administrator of the Société Radio-Normandie, ousted from the board by Fernand Le Grand) because Brusset had concluded an agreement on the sly with the IBC to take revenge on his former director.

End of September 1939 until January 3, 1940: broadcasts in English begin from the old transmitter of Fécamp still operational on 212.6 m under the name "Radio International". The broadcasts organized by the IBC consist of recorded programs without mentioning the advertisers. The slogan of the radio is "the station behind the (enemy) lines". The broadcasts take place from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. the station broadcasts programs for the British troops engaged on the continent.

The broadcasts which were entitled "Tommy's quarter-hour", were directed by Ambassador Jacques Fouques-Duparc, and Countess Andrée de Fels. In the run-up to the war, at the end of July 1939, the Radio-International company had acquired

ownership of the former Radio-Normandie station installed on the cliff of Fécamp in a wooden building, in the style of a Norman chalet. At the request of the French government, on the initiative of Mr. Jean Mistler, President of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, the transmitter was planned to be transferred with its wavelength of 212.6 meters, to the station called Radio-International (in Épone). ownership of the former Radio-Normandie station installed on the cliff of Fécamp in a wooden building, in the style of a Norman chalet. At the request of the French government, on the initiative of Mr. Jean Mistler, President of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, the transmitter was planned to be transferred with its wavelength of 212.6 meters, to the station called Radio-International (in Épone).

Excerpt from René Duval's book : "As this was not the best time to launch an advertising station, Max Brusset's Fécamp transmitter was to be used, under the aegis of the Commissariat Général à l'Information (Jean Giraudoux), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ambassador Fouques Du Parc), and the Chamber's Foreign Affairs Committee (Jean Mistler), for French foreign-language propaganda. But it was the S.I.T. that took all the necessary steps and paid, in particular, for the subscription to the Havas agency's dispatch service

(Correspondence S.I.T.-Havas, from October 1939 to January 1940. Havas archives at the French National Archives).

Issues in Czech were directed by Messrs. Mazarick and Osusky, those in Austrian by H.H. Archduke Otto of Habsburg. The name of the editor-in-chief of the Polish broadcasts cannot be determined from the archives.

The second act of Max Brusset's play - the plot of which he modifies as events unfold - consists in transferring the 10 kW transmitter from Fécamp to Epône, for technical reasons of military security. The transmitter's power was considerably increased by the addition of specially ordered Thomson-Houston equipment, and the station's title was changed from Radio-International-Fécamp to Radio-International-Epône. At this point, the leaders of the federation of private radio stations began to ask serious questions. To calm them down, Max Brusset wrote a long letter on March 9, 1940, to Jacques Tremoulet, vice-president of the federation, in which he forbade anyone to question his word, and in which he specified: "The installation of the station at Epône, in the Paris region, will be carried out in agreement with and by order of the government, for a purpose of general interest and French propaganda, which it is not for anyone to discuss, and whose realization cannot be attacked. This station will not broadcast in French at any time, and will not carry any French commercial advertising. It is intended solely for foreign-language broadcasts, under the control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the General Commissariat for Information, at whose disposal it has been placed.

Max Brusset cleverly mentions only French advertising... he's not lying for a second, since if the transmitter can become commercial after hostilities, it will be destined for English advertising.

But the arrival of the Germans in June 1940 sounded the death knell for his fine hopes." |

Max Brusset resta propriétaire du château d'Epone

(près de Mantes-la-Jolie), bien que Plugge ait toujours prétendu qu'il lui appartenait de droit.

Le château sera démoli par les Allemands en 1944

Max Brusset remained the owner of the Château d'Epone (near Mantes-la-Jolie), although Plugge always claimed that

it was his by right. The château was demolished by the Germans in 1944

| Epone = 40 km de Paris / 40 km from Paris

Extrait de la plaquette historique de la ville d'Epone https://epone.fr/sites/epone/files/document/2020-06/parcours-epone-historique.pdf

"En 1939, devenu propriété de Monsieur Max Brusset "En 1939, devenu propriété de Monsieur Max Brusset  (1902-1992), un des administrateurs de la société « RADIO NORMANDIE », le château est occupé par les Allemands qui y installent un émetteur de leur radio « CALAIS ONE ». À L’arrivée des Alliés, le 18 août 1944, les Allemands partent en dynamitant le château. Grand résistant (groupe Combat), ainsi que sa femme, arrêtés, sauvés in extremis de la mort, il fera raser les ruines du château et fera aménager en résidence de campagne les communs. (1902-1992), un des administrateurs de la société « RADIO NORMANDIE », le château est occupé par les Allemands qui y installent un émetteur de leur radio « CALAIS ONE ». À L’arrivée des Alliés, le 18 août 1944, les Allemands partent en dynamitant le château. Grand résistant (groupe Combat), ainsi que sa femme, arrêtés, sauvés in extremis de la mort, il fera raser les ruines du château et fera aménager en résidence de campagne les communs.

En 1978, le domaine est vendu. La commune d’Épône devient propriétaire d’une partie du parc autour du Temple de l’Amitié et de la maison qui devient, le 28 novembre 1981, le Centre culturel Dominique DE ROUX, restauration et inauguration des nouveaux locaux le 7 septembre 2002 sous la présidence de Monsieur Pierre Amouroux maire d’Épône et Vice-Président du Conseil Général des Yvelines".

"In 1939, having become the property of Mr. Max Brusset (1902-1992), one of the directors of the company "RADIO NORMANDIE", the castle was occupied by the Germans who installed a transmitter for their radio "CALAIS ONE" there. When the Allies arrived on August 18, 1944, the Germans left by dynamiting the castle. A major resistance fighter (Combat group), as well as his wife, arrested, saved in extremis from death, he had the ruins of the castle razed and had the outbuildings converted into a country residence. In 1978, the estate was sold. The commune of Épône became the owner of part of the park around the Temple of Friendship and the house which became, on November 28, 1981, the Dominique DE ROUX Cultural Center, restoration and inauguration of the new premises on September 7, 2002 under the presidency of Mr. Pierre Amouroux, Mayor of Épône and Vice-President of the General Council of Yvelines". "In 1939, having become the property of Mr. Max Brusset (1902-1992), one of the directors of the company "RADIO NORMANDIE", the castle was occupied by the Germans who installed a transmitter for their radio "CALAIS ONE" there. When the Allies arrived on August 18, 1944, the Germans left by dynamiting the castle. A major resistance fighter (Combat group), as well as his wife, arrested, saved in extremis from death, he had the ruins of the castle razed and had the outbuildings converted into a country residence. In 1978, the estate was sold. The commune of Épône became the owner of part of the park around the Temple of Friendship and the house which became, on November 28, 1981, the Dominique DE ROUX Cultural Center, restoration and inauguration of the new premises on September 7, 2002 under the presidency of Mr. Pierre Amouroux, Mayor of Épône and Vice-President of the General Council of Yvelines".

Histoire de famille en pays Mantois Gilles Bodin : https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02288266/file/MemoireGenealogie_Bodin_Gilles_2019_DUMAS.pdf

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, après la débâcle de 1940, Epône est occupée comme le reste des Yvelines à partir du 13 juin 1940. Les Allemands s'emparent de l'émetteur privé qui vient d'être installé dans le château par Radio-Normandie*, pour diffuser leur propagande vers la Grande-Bretagne. En 1944, les bombardements alliés détruisent la gare SNCF et les ponts sur la Seine. Le 18 août, les Allemands font sauter le château et l'émetteur radio. Il ne reste que les dépendances, transformées plus tard en centre culturel. Le lendemain, la ville est libérée par les premiers éléments de la 79e division d'infanterie de l'armée américaine. Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, après la débâcle de 1940, Epône est occupée comme le reste des Yvelines à partir du 13 juin 1940. Les Allemands s'emparent de l'émetteur privé qui vient d'être installé dans le château par Radio-Normandie*, pour diffuser leur propagande vers la Grande-Bretagne. En 1944, les bombardements alliés détruisent la gare SNCF et les ponts sur la Seine. Le 18 août, les Allemands font sauter le château et l'émetteur radio. Il ne reste que les dépendances, transformées plus tard en centre culturel. Le lendemain, la ville est libérée par les premiers éléments de la 79e division d'infanterie de l'armée américaine.

* Non, "Radio Normandie" n'est en rien impliquée dans cette entreprise initiée par Max Brusset et sa société S.I.T. avec la duplicité de l'International Broadcasting Company de Londres. Au contraire, « Radio-International-Epone » devait concurrencer les émissions anglophones de Radio Normandie. Mais cette opération fut contrariée par l'invasion allemande de 1940. (Ndw)

During World War II, after the debacle of 1940, Epône was occupied like the rest of Yvelines from June 13, 1940. The Germans seized the private transmitter that had just been installed in the castle by Radio-Normandie*, to broadcast their propaganda to Great Britain. In 1944, Allied bombings destroyed the SNCF railway station and the bridges over the Seine. On August 18, the Germans blew up the castle and the radio transmitter. Only the outbuildings remained, which were later converted into a cultural center. The next day, the town was liberated by the first elements of the 79th Infantry Division of the American Army. During World War II, after the debacle of 1940, Epône was occupied like the rest of Yvelines from June 13, 1940. The Germans seized the private transmitter that had just been installed in the castle by Radio-Normandie*, to broadcast their propaganda to Great Britain. In 1944, Allied bombings destroyed the SNCF railway station and the bridges over the Seine. On August 18, the Germans blew up the castle and the radio transmitter. Only the outbuildings remained, which were later converted into a cultural center. The next day, the town was liberated by the first elements of the 79th Infantry Division of the American Army.

* No, "Radio Normandie" was in no way involved in this enterprise that was initiated by Max Brusset and his company S.I.T. with the duplicity of the International Broadcasting Company of London. On the contrary, "Radio-International-Epone" was supposed to compete with the English-language broadcasts of Radio Normandie. But this operation was thwarted by the German invasion in 1940. (Ndw) |

|

| |

Les présentateurs de Radio International

émissions en anglais

George Busby Manager - (His secretary was Beryl Muir)

Bob Danvers Walker

Une fois rentré à Londres en 1940, il a appris

que son nom figurait sur une liste noire des

personnes à "éliminer" par la Gestapo

|

Philip Slessor

Producteur et annonceur, il participe

au début à Radio International mais sur sa demande,

sera remplacé par Roy Plomley

|

Roy Plomley, speaker et producteur

|

Charles Chalmers Maxwell a participé

aux émissions de Radio International

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/obituary-charles-maxwell-1170049.html

|

David Davies

|

Godfrey Holloway

|

Egalement présents : Ralph Hurcombe, Maurice Griffith - Techniciens / Technical staff : Cilff Sandall - Timmy Timms

|

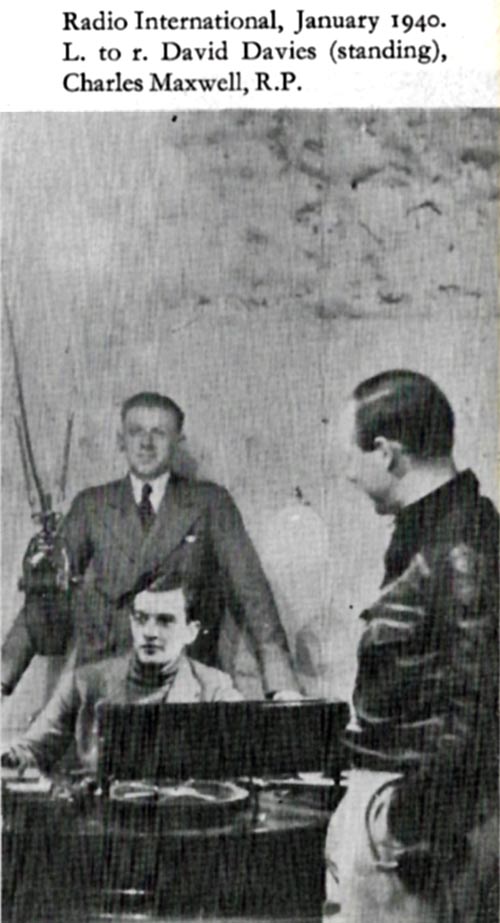

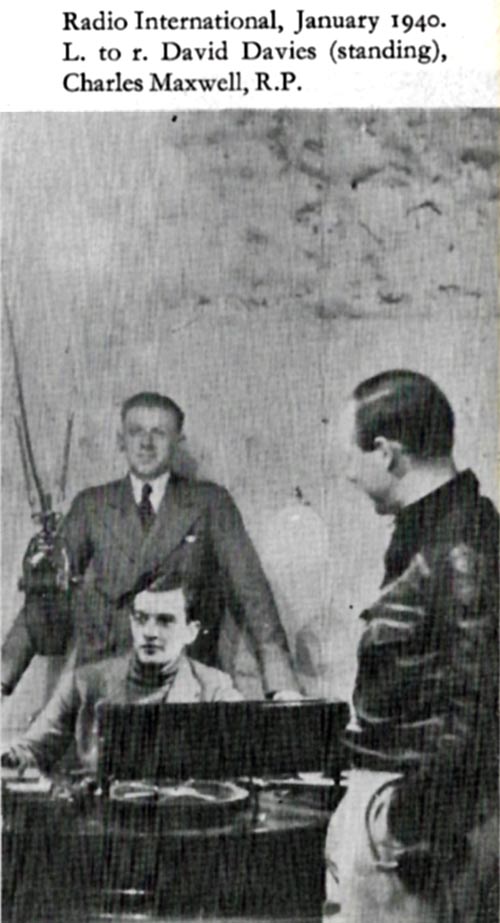

De g. à dr. David Davies (debout), Charles Maxwell, Roy Plomley en janvier 1940

|

bauer

émissions AUTRICHIENNES, TCHèQUES, polonaises...

La programmation de jour était en anglais, de 7h00 à 20h00, puis l'émetteur est cédé

à la diffusion tchèque pendant deux heures, suivies à 22h00 de deux autres heures

de transmissions par la station autrichienne Freedom, pour fermer à minuit.

Daytime programming was in English, from 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., then the transmitter was handed

over to Czech broadcasting for two hours, followed at 10:00 p.m. by another two hours

of transmissions by the Austrian station Freedom, closing at midnight.

La station autrichienne "Freedom"

(Liberté)

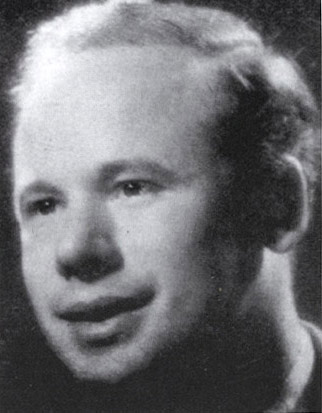

Dr Robert Albert Bauer

(la photo date de 1942 est prise dans les studios de la Voix de l'Amérique)

Mr Bauer était connu comme animateur radio sous le nom de code « Rudolf ».

(The photo dates from 1942 and was taken in the Voice of America studios.)

Mr. Bauer was known as a radio host under the code name "Rudolf."

|

Après son séjour à Fécamp, Robert Bauer

avait rejoint les micros de la "Voix de l'Amérique".

Voici un extrait d'interview de Robert Bauer

donnée en 1989 où il évoque son passage

à Radio International Fecamp.

(Association d'études et de formation diplomatiques -

Projet d'histoire orale des affaires étrangères) |

After his time in Fécamp, Robert Bauer

joined the "Voice of America" radio station.

Here is an excerpt from a 1989 interview

with Robert Bauer, where he discusses

his time at Radio International Fecamp.

(Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training -

Foreign Affairs Oral History Project) |

|

Date

d'interview : 4 octobre 1989 par Cliff Groce

Q : Bob, dans quelles circonstances avez-vous rejoint la Voix de

l'Amérique ?

Contexte : Naissance en Autriche. Émissions radiophoniques

antinazies en Tchécoslovaquie, en France, puis sur Crosley Radio

aux États-Unis en 1939.

BAUER : Vous savez probablement que je suis né en Autriche, que

j'ai milité dans le mouvement antinazi et que je suis devenu

réfugié à l'arrivée des nazis. J'étais d'abord en

Tchécoslovaquie, puis en France. Et c'est en France, en 1939,

que j'ai commencé à travailler à la radio. Par hasard, j'étais

avocat. Nous travaillions sur une station de radio antinazie,

créée par les Français, avec les Tchécoslovaques. Nous formions

la section autrichienne de la Radiodiffusion de la Liberté de

cette station antinazie.

Q : Émissions en Autriche.

BAUER : En Autriche. Nous n'étions que quelques-uns. Le chef de

la section antinazie autrichienne s'appelait Martin Fuchs.

Q : Quand était-ce ?

BAUER : C’était en 1939.

Q : Juste après le début de la guerre.

BAUER : Pour les Français, les États-Unis n’étaient pas encore

impliqués. J’ai donc dirigé la station autrichienne de radio

liberté à Fécamp, en Normandie. Puis, après la chute de la

France, nous sommes partis aux États-Unis. Si je vous raconte

cela, c’est que plus tard, j’ai fait une tournée de conférences.

Certaines personnes connaissaient mon travail contre les nazis

et m’ont donc envoyé faire une tournée de conférences dans

divers lieux, comme des Rotary Clubs, pour parler de la

situation en Europe (...) |

INTERVIEW

date : October 4, 1989 by Cliff Groce

Q : Bob, what were the circumstances of your joining the Voice

of America ?

Background : Austrian Birth. Anti-Nazi Radio Broadcasting In

Czechoslovakia, France, and Ultimately Over Crosley Radio In

U.S. in 1939

BAUER : You probably know that I was born in Austria, and was in

the anti-Nazi movement and became a refugee when the Nazis came.

I was first in Czechoslovakia and then in France. And in France,

in '39, I got into radio. By chance, I was a lawyer. And we were

in an antiNazi radio station, set up by the French, together

with the Czechoslovaks. We were the Austrian Freedom

Broadcasting section of this anti-Nazi station.

Q: Broadcasting into Austria.

BAUER: Into Austria. There were only a few of us. The chief of

the Austrian anti-Nazi outfit was a man named Martin Fuchs.

Q: When was this ?

BAUER: This was 1939.

Q: Just after the war began.

BAUER: For the French, the States were not in it yet. So I ran

this Austrian Freedom Broadcasting Station in Fécamp, Normandy.

Then when France fell we made our way to the United States. The

reason I tell you that is that later on, I went on a lecture

tour. Some people had known about my work against the Nazis, and

so they sent me on a lecture tour to various places, like Rotary

Clubs and so forth, to talk about what was happening in Europe

(...) |

Robert Bauer était originaire d'Autriche, où il a obtenu des diplômes d'économie et de droit à l'Université de Vienne.

Il y a débuté sa carrière d'avocat dans les années 1930. Après l'annexion de l'Autriche par les nazis, il s'est enfui à Prague et a rejoint le mouvement de l'Autriche libre.

En 1939 et 1940, il a été rédacteur en chef de la station de radio autrichienne « Liberté » (Radio International Fécamp), une station de camouflage du Corps expéditionnaire britannique.

Il était actif dans le mouvement antinazi autrichien contre Hitler avant la Seconde Guerre mondiale et, en 1980, il a reçu le Grand Ordre d'honneur d'argent de la République d'Autriche pour ses services lors de la libération de l'Autriche. |

Robert Bauer was originally from Austria, where he earned degrees in economics and law from the University of Vienna. He began his career as a lawyer there in the 1930s. After the Nazi annexation of Austria, he fled to Prague and joined the Free Austria movement.

In 1939 and 1940, he was editor-in-chief of the Austrian radio station "Liberty" (Radio International Fécamp), a covert station for the British Expeditionary Force.

He was active in the Austrian anti-Nazi movement against Hitler before World War II and, in 1980, was awarded the Grand Silver Order of Honour of the Republic of Austria for his services during the liberation of Austria. | | |

Robert Albert Bauer (né en Autriche, citoyen américain, 1910 - 27 septembre 2003), était un officier du service extérieur américain, un animateur de radio antinazi, un annonceur de Voice of America (VOA) et un auteur et éditeur d'affaires internationales, dont la carrière diplomatique s'est étendue de la Seconde Guerre mondiale à la guerre froide. Il a fui les nazis à trois reprises - de Vienne et de Prague en 1938 et de Paris en 1940.

Maître des dialectes argotiques autrichiens, Bauer diffusa anonymement des informations antinazies en allemand sur la station autrichienne de radio-liberté de Fécamp, en Normandie, dans les années 1930. (de sept 1939 à jan 1940)

Il imitait souvent Adolf Hitler et se moquait de lui dans des reportages humoristiques. La presse le surnommait « Rudolph ». Militant dans le mouvement antinazi autrichien contre Hitler avant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il reçut en 1980 le Grand Ordre d'argent de la République d'Autriche pour services rendus lors de la libération de l'Autriche.

Ses émissions attirèrent l'attention d'Hitler, qui le plaça sur la liste des personnes les plus recherchées par les nazis.

Le jour même de l'occupation de l'Autriche par les nazis lors de l'Anschluss, le 12 mars 1938, Bauer monta dans un train avec une valise et quitta l'Autriche. Il ne revit jamais sa mère. Il s'enfuit en Tchécoslovaquie et rejoignit le Mouvement pour l'Autriche Libre à Prague, où il travailla comme reporter au New York Times de 1938 à 1939, couvrant les régions des Sudètes et des Carpates ukrainiennes .

À Prague, il rencontra Maria von Kahler (née en 1920), qui craignait qu'elle et ses parents juifs assimilés, Felix et Lilli von Kahler, soient arrêtés par les nazis. Les von Kahler étaient une riche famille austro-hongroise germanophone qui possédait des sucreries dans ce qui allait devenir la Tchécoslovaquie après 1919. Leur maison pragoise, située au 18, rue Sous les Châtaignes, et leur château de campagne, Svinare, furent plus tard confisqués par les nazis, puis pris par les communistes russes.

Après les accords de Munich, la Tchécoslovaquie se retrouve encerclée par l'Allemagne sur trois côtés. L'Allemagne nazie envahit les Sudètes, qui formaient les frontières naturelles de la Tchécoslovaquie, le 1er octobre 1938. Bauer et les von Kahler s'enfuirent séparément à Paris et se retrouvèrent plus tard à Paris, où Maria von Kahler le rejoignit pour travailler pour la station de radiodiffusion clandestine autrichienne "Liberté" à Fécamp, en Normandie, de 1939 à 1940. Bauer était directeur de la station autrichienne de la liberté, émettant depuis la Normandie jusqu'à la veille de l'invasion de la France au printemps 1940. La station fut bombardée et détruite par l'Allemagne quelques jours après leur fuite.(1)

Les Bauer et von Kahler ont fui la France avant l'armée allemande après la rupture de la ligne Maginot en juin 1940, empruntant la même route d'exode vers Bayonne, empruntée par environ quatre millions de personnes en voiture, à vélo et à pied. Cet itinéraire a été mis en scène dans le film Casablanca de 1942.

Bauer et Maria von Kahler se sont mariés au Portugal en août 1940 et ont immédiatement embarqué sur le vapeur portugais SS Quanza pour immigrer aux États-Unis. Le SS Quanza fut le premier navire de réfugiés à fuir l'Europe nazie.

(Wikipedia)

(1) Faux. Il y a confusion. La station de Fécamp n'a jamais été bombardée. C'est l'armée française qui a sabordé les installations le 10 juin 1940, veille de l'invasion allemande. L'auteur de ce texte confond avec l'émetteur de Louvetot qui lui, a été détruit bien après, par l'armée nazie au moment de sa retraite en août 1944

| Robert Albert Bauer (born Austria, American citizen, 1910 September 27, 2003), was an American Foreign Service officer, anti-Nazi radio host, Voice of America (VOA) announcer, and international affairs author and editor, whose diplomatic career spanned from World War II to the Cold War. He fled the Nazis three times—from Vienna and Prague in 1938 and from Paris in 1940.

A master of Austrian slang dialects, Bauer anonymously broadcast anti-Nazi information in German on the Austrian Radio Freedom station in Fécamp, Normandy, in the 1930s. (From Sept 1939 to January 1940)

He often imitated Adolf Hitler and mocked him in humorous reports. The press nicknamed him "Rudolph." An activist in the Austrian anti-Nazi movement against Hitler before World War II, he was awarded the Grand Silver Order of the Republic of Austria in 1980 for services rendered during the liberation of Austria.

His broadcasts caught the attention of Hitler, who placed him on the Nazis' most-wanted list.

On the very day the Nazis occupied Austria in the Anschluss, March 12, 1938, Bauer boarded a train with a suitcase and left Austria. He never saw his mother again. He fled to Czechoslovakia and joined the Free Austria Movement in Prague, where he worked as a reporter for the New York Times from 1938 to 1939, covering the Sudetenland and Carpathian regions of Ukraine.

In Prague, he met Maria von Kahler (born 1920), who feared that she and her assimilated Jewish parents, Felix and Lilli von Kahler, would be arrested by the Nazis. The von Kahlers were a wealthy German-speaking Austro-Hungarian family who owned sugar factories in what would become Czechoslovakia after 1919. Their Prague home at 18 Rue Sous les Châtaignes and their country castle, Svinare, were later confiscated by the Nazis and then taken over by the Russian communists.

After the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia found itself surrounded by Germany on three sides. Nazi Germany invaded the Sudetenland, which formed the natural borders of Czechoslovakia, on October 1, 1938. Bauer and the von Kahlers fled separately to Paris and later reunited in Paris, where Maria von Kahler joined him to work for the clandestine Austrian "Freedom" Broadcasting Station in Fécamp, Normandy, from 1939 to 1940. Bauer was director of the Austrian Freedom Station, broadcasting from Normandy until the eve of the invasion of France in the spring of 1940. The station was bombed and destroyed by Germany a few days after their escape.(1)

The Bauers and von Kahlers fled France ahead of the German army after the breach of the Maginot Line in June 1940, taking the same exodus route to Bayonne, used by an estimated four million people by car, bicycle, and on foot. This route was depicted in the 1942 film Casablanca.

Bauer and Maria von Kahler married in Portugal in August 1940 and immediately boarded the Portuguese steamer SS Quanza to immigrate to the United States. The SS Quanza was the first refugee ship to flee Nazi Europe.

(Wikipedia)

(1) False. There is confusion. The Fécamp station was never bombed. It was the French army that scuttled the installations on June 10, 1940, the eve of the German invasion. The author of this text is confusing it with the Louvetot transmitter, which was destroyed much later by the Nazi army during its retreat in August 1944. |

Pour en savoir plus :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Albert_Bauer

La section tchèque

Professeur Milan Janota

Journaliste tchèque

09. 08. 1896 - Čadca - 21. 06. 1957 - Žilina

Milan Janota a étudié le journalisme à Paris. Il a travaillé comme rédacteur dans plusieurs journaux. En tant que rédacteur diplomatique, il a travaillé en France, en Afrique du Nord, en Amérique centrale et à Cuba. De retour dans sa ville natale, il a été rédacteur en chef de Kysucký priekopník. Il est l'auteur de plusieurs publications et de récit de voyage « Po ostrovoch Karibského mora » (1958).

| Milan Janota studied journalism in Paris. He worked as an editor for several newspapers. As a diplomatic editor, he worked in France, North Africa, Central America, and Cuba. Upon returning to his hometown, he was editor-in-chief of Kysucký priekopník. He is the author of several publications and the travelogue "Po ostrovoch Karibského mora" (1958). |

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Les émissions en tchèque sont dirigées par MM. Masarick et Osusky,

celles en autrichien le sont par S.A. l’archiduc Otto de Habsbourg.

.jpg)

Jan Masarick Stephan Osusky Otto de Habsbourg

1886-1948 1889-1973 1912-2011

La section polonaise

Les archives ne permettent pas de déterminer le nom du rédacteur en chef des émissions polonaises.

...

|

|

La station de l’IBC à Fécamp commence donc ses émissions fin septembre – début octobre, jouant des disques de musique légère ou musique de danse pendant la journée jusqu’à 19 h 15. Tous les quarts d’heure, on entend le vieux carillon de « Radio Normandy » suivi de l’annonce « This is the International Broadcasting Station, preparing a new service ».

La station de l’IBC à Fécamp commence donc ses émissions fin septembre – début octobre, jouant des disques de musique légère ou musique de danse pendant la journée jusqu’à 19 h 15. Tous les quarts d’heure, on entend le vieux carillon de « Radio Normandy » suivi de l’annonce « This is the International Broadcasting Station, preparing a new service ».

du nouvel émetteur. Peu de temps après son arrivée, Roy Plomley était invité à les rejoindre. L’idée était de mettre en place un programme hebdomadaire destiné à l’instruction des troupes britanniques sur les coutumes françaises et l’apprentissage de quelques mots et phrases utiles. Le programme appelé “La demi-heure du Tommy”, fut confié à Roy avec l’assistance de conseillers titrés et cultivés. L’enregistrement s’effectuerait chaque semaine dans les studios du Poste Parisien

(à Paris) pour être diffusé depuis Fécamp. Puis la demi-heure est réduite au "Quart d'heure du Tommy". La station a commencé ses émissions fin septembre 1939 sous le nom de "Radio International". Cela a aussitôt donné lieu à une série de correspondances, classées secrètes, entre diverses autorités en Angleterre. Alors que le ministère de l'Air voulait fermer la radio parce qu'elle ne faisait pas partie d'un groupe de stations synchronisées et pouvait être utilisée comme balise par les avions ennemis, le GPO (Ministère britannique des Postes) et la BBC avaient leurs propres raisons de souhaiter la fermeture de Fécamp, certains affirmaient que la BBC fournirait un meilleur service, alors que d'autres pensaient que Fécamp faisait un bon travail. Cependant, la valeur du divertissement fut jugée négligeable par rapport au préjudice causé pour la sécurité. En conséquence, la fermeture définitive de Fécamp fut ordonnée le 3 janvier 1940 par les autorités françaises. La mélodie de clôture de Radio International

“Keep the Home Fires Burning d'Ivor Novello” était entendue pour la dernière fois.

du nouvel émetteur. Peu de temps après son arrivée, Roy Plomley était invité à les rejoindre. L’idée était de mettre en place un programme hebdomadaire destiné à l’instruction des troupes britanniques sur les coutumes françaises et l’apprentissage de quelques mots et phrases utiles. Le programme appelé “La demi-heure du Tommy”, fut confié à Roy avec l’assistance de conseillers titrés et cultivés. L’enregistrement s’effectuerait chaque semaine dans les studios du Poste Parisien

(à Paris) pour être diffusé depuis Fécamp. Puis la demi-heure est réduite au "Quart d'heure du Tommy". La station a commencé ses émissions fin septembre 1939 sous le nom de "Radio International". Cela a aussitôt donné lieu à une série de correspondances, classées secrètes, entre diverses autorités en Angleterre. Alors que le ministère de l'Air voulait fermer la radio parce qu'elle ne faisait pas partie d'un groupe de stations synchronisées et pouvait être utilisée comme balise par les avions ennemis, le GPO (Ministère britannique des Postes) et la BBC avaient leurs propres raisons de souhaiter la fermeture de Fécamp, certains affirmaient que la BBC fournirait un meilleur service, alors que d'autres pensaient que Fécamp faisait un bon travail. Cependant, la valeur du divertissement fut jugée négligeable par rapport au préjudice causé pour la sécurité. En conséquence, la fermeture définitive de Fécamp fut ordonnée le 3 janvier 1940 par les autorités françaises. La mélodie de clôture de Radio International

“Keep the Home Fires Burning d'Ivor Novello” était entendue pour la dernière fois.

All the members of the IBC were gathered in Fécamp in the presence of Richard Meyer, director of the IBC, who announced that no future employment with the IBC was to be expected and that they should make their arrangements. Bob Danvers-Walker returned to London and got a job at Pathé News. Others, such as Charles Maxwell and Tom Ronald joined the BBC.

All the members of the IBC were gathered in Fécamp in the presence of Richard Meyer, director of the IBC, who announced that no future employment with the IBC was to be expected and that they should make their arrangements. Bob Danvers-Walker returned to London and got a job at Pathé News. Others, such as Charles Maxwell and Tom Ronald joined the BBC.

Les installations vacantes à Fécamp depuis le transfert à Louvetot le 12.12.1938

Les installations vacantes à Fécamp depuis le transfert à Louvetot le 12.12.1938  Tommy », étaient dirigées par l’ambassadeur Jacques Fouques-Duparc

Tommy », étaient dirigées par l’ambassadeur Jacques Fouques-Duparc

ownership of the former Radio-Normandie station installed on the cliff of Fécamp in a wooden building, in the style of a Norman chalet. At the request of the French government, on the initiative of Mr. Jean Mistler, President of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, the transmitter was planned to be transferred with its wavelength of 212.6 meters, to the station called Radio-International (in Épone).

ownership of the former Radio-Normandie station installed on the cliff of Fécamp in a wooden building, in the style of a Norman chalet. At the request of the French government, on the initiative of Mr. Jean Mistler, President of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, the transmitter was planned to be transferred with its wavelength of 212.6 meters, to the station called Radio-International (in Épone).

.jpg)